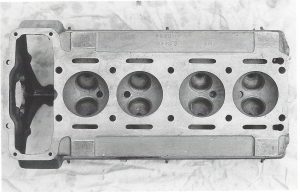

Four Cylinder 2 Litre XK Engine – 1948

1948 Jaguar XK 4 Cylinder Engine

On display in the Collections Centre at Gaydon we have one of only 4 remaining, four-cylinder XJ/XK engines that were built during the development of the XK engine. It has the same overall configuration as the six-cylinder XK engine: chain driven twin overhead camshafts; two valves per cylinder; hemispherical combustion chambers and twin SU carburettors.

During the 1930s William Lyons had developed the Swallow Coachbuilding Company to become a mainstream motorcar manufacturer. From the Standard Motor Company came purpose-built chassis and engines for the range of SS and SS Jaguar models. World War Two put a stop to private vehicle production in Britain and all manufacturers turned to war work. SS Cars was no exception and they repaired aircraft as well as supplying various sidecars and trailers to the armed forces. Lyons started planning a 100 mph saloon that would be available post-war which would need a new, more powerful engine. One that would set a new standard in power plants and he also understood the importance of it looking attractive.

Lyons was fortunate to have three very talented engineers working for him: William Heynes, Walter Hassan and Claude Baily. They spent the hours during fire-watching duties discussing the requirements and planning a series of engines. In the pre-war years the small four-cylinder 1½ litre saloon sold in larger numbers than the six-cylinder 2½ litre and 3½ litre models. Lyons foresaw a period of austerity after the war when there would be a greater demand for a smaller engine. Consequently, both four and six cylinder versions were envisaged.

Two four-cylinder engines were developed side-by-side, coded XF and XG. The latter appears to have been bench run first in 1943 and was a four-cylinder unit with a bore and stroke of 76 x 106 mm giving 1,776 cc. Heynes wrote that it was ‘really a conversion of the existing Jaguar four cylinder push rod engine; the head and valve gear, and also the inlet ports were based on the BMW 328 cylinder head. In the Jaguar design the push-rods and the rockers were found to be difficult to silence to the standard necessary for a touring saloon engine.’ The XG consisted of a newly-designed aluminium alloy cylinder head with hemispherical combustion chambers mated to the Standard 1½ litre block, which had been stretched from 1,608 cc (69 x 106 mm) to 1,776 cc for the 1938 model range. All the valves of the XG were operated from the existing single camshaft, tappets and modified pushrods, up to rockers situated in the near-side rocker box. Hassan described the inlet ports as being ‘almost vertical, formed in pairs and connected by a large balanced passage and fed by two 1½ inch bore SU carburettors.’

The XF twin-cam engine was first run on 27 November 1944 and as Heynes later wrote: ‘This engine was the first example of a double overhead cam (DOHC) engine made. It was designed primarily to prove the type of head and valve gear, which it did very adequately. We found the crankshaft design was inadequate for the very high speed at which the engine would otherwise operate. Nevertheless, the engine fulfilled its function and gave a lot of sound practical data’. The XF was run on ‘Pool’ petrol – a mix of various brands, blends and octane ratings mixed or ‘pooled’ for use in the rationed private sector. Running at 2,000 rpm it gave 23.3 bhp and 56.3 bhp at 5,000 rpm on twin SU carburettors, but no fan or gearbox was attached. This engine was not without its problems as Hassan reports: ‘After a few minutes, oil was trapped under the valve tappets causing a loud hammering noise. The valve gear was taken down and 3/16” was removed from the bottom of the tappets so that the breather ports in the tappet guides were uncovered at full valve lift.’ Some damage to the camshaft and cam followers was noted and repaired in time for trials to continue. However, it failed on 8 December, when ‘The flywheel securing bolts sheared before the test could be completed and the engine was removed to the experimental shop for strip and examination.’

Underside of cylinder head showing hemispherical combustion chambers

When the XF engine was rebuilt and returned to the test bench it was rated at 1,732 cc. Tests had established that the DOHC arrangement of the XF was the best. Both XF and XG were side-lined in favour of another four-cylinder engine design with a bore and stroke of 80 x 98mm and 1,996 cc.

Given the code XJ, this is generally regarded as the real forerunner to the XK engine. Most of the experiments with port and head design were carried out on the XJ, as were trials with valve gear and camshaft drives, resulting in its final configuration of: a pair of chain driven, overhead cams, two valves per cylinder and hemi-spherical combustion chambers.

1948 Jaguar XK 4 Cylinder Engine on display in the Collections Centre at Gaydon

The first XK engine was not run until October 1945. This was ‘XK Engine No. 1’ – a four-cylinder unit with a three-bearing crankshaft, a bore and stroke of 76 x 98 mm and a capacity of 1,790 cc. The engine was still a small capacity unit similar to the XF, XG and even the pre-war Standard-SS Jaguar units.

However, at this stage, even though Heynes mentions a six-cylinder version, tests appear to have been carried out on the four-cylinder XK which gave 76 bhp during early trials and later 83 bhp.

Heynes wrote that the XJ was changed so many times that no accurate drawing could be produced to represent the engine at any stage until it was in a settled state.

The design was quickly moved on through to a six-cylinder version with a bore and stroke of 83 x 106 mm with a capacity of 3,182 cc and then on to the production XK engine.

A six cylinder XK was run for the first time on 15 September 1947 recording a power output of 142 bhp at 5,000 rpm. It was apparent that the six-cylinder layout was a much better and much smoother configuration than the four cylinder. Jaguar did not have the resources to develop both engines and work concentrated on the six-cylinder.

The 4 cylinder version of the XK engine was never considered smooth enough to power the smaller saloons and work commenced on shrinking the dimensions of the six cylinder XK engine. In July 1951, tests were run on an engine with a bore and stroke of 88 x 66 mm for a capacity of 1,986 cc. Figures record 113 bhp at 6,000 rpm, not quite what was hoped for by Jaguar. However, by early 1954, an engine with a bore and stroke of 83 x 76 mm for a capacity of 2,483 cc was producing 155 bhp at 6,000 rpm on the test bench. This was ideal for the small unitary construction saloon that was nearing completion and gave the options of the 2.4 and 3.4 litre engines. The compact saloon was launched in 1955 as the Jaguar 2.4 (retrospectively known as the Mark I, since the launch of the Mark II in 1959). The 2.4 litre engine used the same cylinder head as the 3.4 litre engine, another reason not to pursue the 4 cylinder option.

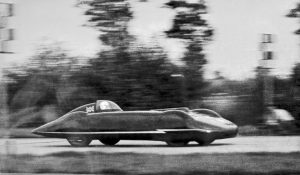

Goldie Gardner’s record breaking run at Jabbeke

Goldie Gardner’s Record breaking MG

One of the four-cylinder XJ engines (80 x 98 mm 1,996 cc) was fitted with modified pistons giving a 12:1 compression ratio and this was loaned to Major A.T.G. Goldie Gardner for use in his MG Special. Gardner drove this to over 176.6 mph (109 km/hr) at Jabbeke, near Ostend, in Belgium to set a new speed record in the 2-litre class. He broke the flying mile, kilometre and five-kilometre Class E records. At the time it was considered remarkable that his engine was unsupercharged. The new records were: mile 173.678 mph, kilometre 177.112 mph and five kilometres 170.523 mph.

Engine Test Reports

From surviving engine test sheets in the JDHT archives, we are able to see that in May 1948 one of the four-cylinder ‘XK’ engines had been assembled as the ‘Gardner Special Engine’ for bench-running trials. However, this unit would appear to be one of the earlier ‘XJ’ engines fitted with modified pistons and with a bore and stroke of 80.5 x 98 mm and with a compression ratio of 12:1 (see below). For convenience and uniformity the unit was referred to as ‘XK’ within the plant.

Jack Emerson of the experimental department was tasked with the testing of the ‘Gardner Special XK’ and his first report to Heynes, Baily and Hassan was issued on August 12, 1948. He notes:

The engine was first assembled, for the purpose of initial running in, to the following specification completed on May 25th.

A new Mark 3 cylinder block with longitudinal rib on the exhaust side. 7/16” waisted head studs with 1/2” foot thread.

Crankshaft with the latest lubrication drilling and sludge traps. Main journals diameter 2.480”. Big end journals diameter 1.854”. Main bearings Standard Vandervell pattern.

Specially designed steel connecting rods.

Weight 1 lb. 13 ozs. 4 drms. Centres 8”

Big end bearings Lead Indium pattern.

Martlet pistons complete with 7/8” gudgeon pins and rings.

Weight 1 lb. 4 ozs. 5 drms.

No. 3 cylinder head complete with valves and springs, chilled iron tappets, camshafts with manifolds as tested on No. 1 prototype engine.

The cylinder head face sealing by Wills Rings and a corrujoint of .010” thickness.

Essolube 30 lubricant with 25% graphited running-in compound added.

Filtration by British Wire internal float filter and exterior Tecalemit SK.9857 with felt element.

Coil ignition with the equipment used in No. 1 prototype engine.

On May 26, the Gardner Special engine was installed on the No. 1 test bed in the Experimental Department at Foleshill. Here it was run for a period of 12 1/2 hours;

‘6 hours slight at 1,000 rpm and 6 1/2 hours quarter load at 1,000, 1,500 and 2,000 rpm respectively with freeness checks carried out at intervals.’

The engine was removed from the test bed on May 28 for inspection before being re-assembled ‘with the final components.’ Emerson was satisfied with the overall condition of the engine which he noted was ‘…in very good condition.’ For the second series of tests the engine was slightly modified with Lead Indium Main bearings and with No. 4 cylinder head fitted. This was with ‘3.2 litre size inlet valves, 1 7/16” dia. Tulip exhaust valves, nitrided steel tappets, special springs and 3/8” lift steel camshafts with 60° overlap.’

Other detail modifications and a change of lubrication were also carried out before the engine was re-installed on No. 1 Test bed on June 4 for running-in to continue on the following day.

On June 5, the engine was run under the same condition for 12 hours before being thoroughly checked over for full load readings. The following day the XK engine was run variously from 5,000 rpm to 6,500 rpm on Methanol fuel to give between 124 bhp and 128 bhp. The results were satisfactory but more tests were required before Mr Emerson was satisfied. It is worth quoting some extracts from his report for June 7:

In view of the compression ratio being below the originally prescribed 14 to 1 it was decided to remove the cylinder head for the face to be machined in order to effect this increase.

.035” was removed, resulting in a chamfer being necessary to clear the piston, also the Doms flats relieved to clear the inlet valves, a compromise of 13.85-1 being obtained.

During the head inspection it was observed that the nitrided steel tappet heads were deeply pitted and considered unfit for further service.

The complete set of used chilled tappets, in excellent condition, were removed from the No. 3 cylinder head, the valve stems modified in length to accommodate Biscuits, the original steel camshafts replaced and the head refitted.

Back on the test bed, the engine was run for fifteen minutes to settle the head and then the load was adjusted to run the engine up to 5.060 rpm where it gave 128.8 bhp. When the load was increased to 6,000 rpm it ran smoothly for a few seconds before vibration set in that resulted in a crankshaft failure. The engine had to be removed and dismantled for inspection, which revealed:

A fracture at No. 1 big end journal rear web fillet.

A crack in the centre main bearing housing.

A bend in No. 1 connecting rod.

The valves in No. 1 cylinder damaged by piston impact.

The remainder of the head undamaged.

Total Running Time

Light 10 hours

Part Load 14 hours 30 minutes

Full Load 40 minutes

TOTAL – 25 hours 10 minutes

In view of this failure, it was decided to defer the assembly of another engine pending crankshaft torsion investigation, by the Metalastik Company.

For the purpose of this test, No. 1 prototype engine was installed on No.1 test bed and the work eventually carried out on June 16th.

As a result of the findings, the crankshaft was now re-designed with increased main and big end journal diameters, the cylinder block was also modified with stiffening webs to the main housings.

Jack Emerson (signed)

The engine was further tested in its rebuilt form during August with various small modifications tried out. For example, in place of the twin SU carburettors, four Amal T.T.10 units were fitted on ‘a special monitoring plate with controls’. This was only tried once and by the next day the SUs were back in place to ‘prove the engine’. After being run for 13 hours 45 minutes the data was collated and the engine declared fit for purpose.

MG Record Car now on display in the British Motor Museum

It was now ready to be fitted to the Gardner Special for the record attempt on 15th September 1948 – just before Jaguar announced the XK120 Super Sports with the six-cylinder XK engine at the Earls Court Motor Show.

The brochure for the XK did offer an XK100 version of the car fitted with the 4 cylinder engine, but none were ever made.

Gardner’s MG Special is now on display in the ‘Record Breakers’ section of the British Motor Museum but fitted with an MG engine.

Author: Tony Merrygold & François Prins

© Text and Images – Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust