Fred Gardner

Sawmill Supervisor and Body Development Shop Manager

1931 Fred Gardner

Fred Gardner, who ran the sawmill at the SS Cars factory in Foleshill, Coventry, from the 1930s, was considered a bit of a rough character with a foul-mouth. Yet he and William Lyons got on well, so much so that he was one of only four people at Jaguar whom Lyons called by his Christian name. The other three were also from the Blackpool days, Jack Beardsley, Cyril Holland and Harry Teather. Together with Cyril Holland he successfully managed to interpret Lyons’ sketches and build styling models from them, staying with Jaguar until well into his 70s, until both men retired.

Gardner was born in Liverpool. His father was a seaman and his mother and several other relations, were a music-hall team. He was the last chairman of Sydenham Palace music hall in Cox Street, Coventry. Influenced by the church, he was a sidesman at Holy Trinity, a strong disciplinarian but he was also regarded as being fair. Gardner first worked for a wheelwright in Stafford and was one of the first “newcomers” to join Swallow after the move from Blackpool to Coventry in 1928.

1931 Foleshill Factory Timber Shop

The sawmill was a vital part of the company as body frames for the Sidecars and Swallow and later SS cars were all built with a wood frame with metal panels fixed and they were made in-house. In the mid 1930’s, although it didn’t threaten the business, the company experienced its first strike – in the sawmill. Gardner’s brother in law was working in the sawmill and the other machinists objected to the fact that he was not in their union and threatened to strike if he was not dismissed. According to William Lyons “Gardner reacted as he did for the next 50 years. He said “not on your life”… whereupon all the men, with the exception of the one involved, walked out and the woodmill came to a standstill”. Surprisingly, despite the unemployment rife in Coventry, no wood machinists were available, but Lyons heard that the situation was different in Scotland. Early that Monday morning he telegraphed a recruitment advertisement to the Glasgow Herald, instructing those interested to telephone Fred Gardner. The response was beyond anything he had hoped for and Gardner was able to pick the best, getting the sawmill working again by the Thursday.

Even in the 1940s when a new accountant, Arthur Thurstans, was appointed it seemed that Gardner ran his sawmill as his own fiefdom – a ‘factory within a factory’ and on one occasion Lyons had to ‘persuade’ him to cooperate with Thurstans.

Since Lyons could not draw, he relied on Cyril Holland and Gardner to interpret any vague sketches he might make. Holland was a draughtsman, coachmaker and master jig-maker and between them they produced and developed the necessary styling bucks.

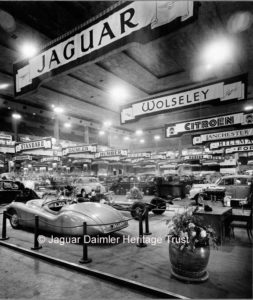

1948 Jaguar XK120

at Earls Court Motor Show

As car manufacture moved away from wooden frames to all steel bodywork, Gardner and his body development shop developed a very close working relationship with the Pressed Steel Company, who were making the steel bodies, often having staff working on their premises.

In mid-1948 Pressed Steel were having problems with the body for the new Mark VII saloon and it became clear to Lyons that it wouldn’t be ready in time for the London Motor Show.

1948 Fred Gardner & William Lyons working on Jaguar Mark V Mock-up

The new XK engine design was now complete and the Company could not, not put in an appearance at the first post-war Motor Show.

Lyons needed a new car to show off his new engine so in a remarkably short time he, Fred Gardner and William Heynes produced a low, two-seat, modern-looking and very stylish sports car – the XK120. Lyons and Gardner arrived at the basic body shape in less than two weeks.

The chassis was a shortened version of the Mark V but the body was all new and it was powered by the new 3.4 litre ‘XK120’ engine with twin SU carburettors.

1950s Fred Gardner

with Concept Coupe

Lyons methods were considered orthodox. There was no initial experiment with scale models as he worked life-size from the start. Once the overall outline made from wire had been agreed, Gardner would substitute a wooden armature, which, under Lyons’ direction, would be planed and shaved to his desired shape. It was quite usual for Lyons to add other wire lines, or pencil lines to this during the day, and Gardner would have the changes ready the following morning.

1950 Fred Gardner

This would continue until Lyons thought the proportions and detail were correct and ‘pleasing to the eye’.

However, after the war Holland who had been made Body Shop Manager, was not happy directing large groups of men, and while Lyons had offered him a much bigger salary than he had anticipated, he did not offer Cyril the written contract he wanted, so he left.

Gardner took over his role as Lyons’ styling “interpreter” and in November 1949, he was appointed superintendent of the sawmill and prototype body department, with the responsibility to look after what was called the Body Development Shop. When Jaguar moved from Foleshill to Browns Lane in 1952, the sawmill moved as well and a new Body Development Workshop was setup alongside. Although the site was new, Gardner’s workshop remained fairly small and only large enough for him to work on one project at a time. The first project for this new workshop was codenamed ‘Utah’, Jaguar’s new unitary construction, compact, saloon which was to emerge as the Jaguar 2.4 in 1955, and then 3.4 in 1957 (retrospectively known as the Mark I). Engineer Bill Heynes set out the basic layout; engine, gearbox, wheelbase and track, and jigs and body panels were made up until the shape was agreed. Once the design was finalised the body was produced by Pressed Steel.

In early 1953, William Lyons enlisted Fred Gardner’s help in building his own design for a racing car. He wanted to build a streamlined sports-racer for possible competition alongside the C-Type, XP/11 and the emerging D-type.

Streamlined Brontosaurus

As usual, Lyons produced the initial sketches and Gardner built a wooden buck on which the all-enveloping body was attached. What emerged in April 1953 was a car that strongly resembled a sketch artist’s idea of a futuristic sports model, the Lyons Special (but christened by some ‘The Brontosaurus’).

The Brontosaurus was tested by Norman Dewis who recorded 100 mph at 5,100 rpm on the nearby Coventry by-pass and found that it responded better than he expected. “There was some transmission vibration at the higher revs and I found the gear change very stiff, the ride was hard, but then we did not have satisfactory suspension compared with the C-Type. I remember when I first saw the car in Fred’s workshop with the front wheels enclosed I thought it must be just for straight-run record breaking, but Fred told me that it was what the Old Man (Lyons) wanted for Le Mans and other races. Anyway, it was fitted with rack and pinion steering and when I turned the wheels to full lock the nearside front fouled the spat.” The Brontosaurus was not successful and after a fire was finally dismantled in 1955.

During 1956 Gardner was working on the XK150 design to replace the now ageing XK140. This wasn’t a new car but rather a re-skin of the old one designed to improve the cabin space, making it more roomy and more comfortable. The car was widened by 4 in. but most of the inner panels were unchanged with changes to bonnet, bootlid, front and rear wings and the doors. The original bonnet pressing continued to be used but the bonnet was split down the middle and a 4 in wide fillet welded in place to give the extra width and become a ‘styling feature’. The wing line was raised and continued along the doors allowing them to incorporate wind up windows which had been missing from the XK140.

The next major project was the large saloon codenamed ‘Zenith’ which was to replace the Mark VIII/IX. This was to be lower and wider than its predecessor, powered by the 3.8 litre version of the XK engine and with the independent rear suspension from the E-type. Again Heynes was responsible for the engineering layout, with many variations tried before arriving at the final body design, with one style on one side of the car and a different one on the other. Much had been learnt from the design and production by Pressed Steel of the ‘Mark I’ and then Mark II (launched in 1958) and approximately £1m was spent on body tooling for Pressed Steel to put the car into production.

Again in 1960 Fred Gardner’s close control of his kingdom was called into question when John Silver, Production Director, was trying to tighten up piecework procedures and costs. He complained to Sir William that Gardner had “became rude and aggressive”. The sawmill had their own way of doing things and didn’t use the system of dockets which was in place to control piecework payments, and there was a general lack of co-operation with other sections of the factory. He acted as both ‘gaffer’ and shop steward in his own department and his close relationship with Sir William seemed to make him immune from many of the standard processes. Having said that, he and his sawmill workers often worked long hours to sort out Lyons’ styling projects.

1962 Fred Gardner (left)and

Sir William Lyons working on the

Daimler SP252 Styling Mock-up

After Jaguar bought Daimler in 1960, William Lyons turned his attention to improving the design of the fibreglass bodied Daimler SP250 sports car by designing a Mark II version. Lyons styled a new body and Gardner built a wood and fibreglass mock-up on an SP250 Chassis. After some changes, a full fibreglass body was mounted on a standard ‘B’ spec chassis, as a running prototype – number 100005 the SP252.

After a feasibility study it was decided not to put this into production and in 1964 production of the Daimler SP250 itself ceased after only 2,654 had been built. SP252 was sold in 1967 and still exists today.

1962 Fred Gardner working on XJ4 Development at Wappenbury Hall

Even when Gardner turned seventy in 1966, he was still attending to Lyons’ needs working on what at the time was Project XJ4. “Sir William would throw his coat on a bench, roll up his sleeves and set to with a rasp, or have me holding nails while he banged them in. Every day he was in there, sometimes with sketches drawn in the middle of the night which he threw on my desk saying: “What about this, Fred?”” While most of this work was completed at Browns Lane some of the initial styling was also done at Wappenbury Hall as Sir William liked to see how the cars would look in their natural environment.

Project XJ4 was launched in 1968 as the new XJ6 Saloon, which Sir William always thought was his finest achievement. It replaced both the compact and large saloons, won car of the year in 1969 and went on to be the basis of eight generations of large saloons.

Fred Gardner’s Legacy

1937 Prince Michael of Romania’s SS Jaguar 3½ Litre in front of the Oak Doors at the Foleshill Factory

When SS Cars moved into the empty First World War shell filling factories in Foleshill, in 1928, they needed complete refurbishment – they didn’t even have electricity. Lyons rejected a local quote for £800 to do the work and used his own labour and asked the labour exchange to send an extra 12 men – 50 turned up. Lyons continued to use his own workers for routine maintenance and building work during slack periods, for a number of years.

Photographs of the Foleshill factory from the 1930s show it with a pair of art deco ‘sunburst’ oak doors on the main entrance. Jaguar moved from Foleshill to Browns Lane in the 1950s and the building was taken over by Dunlop.

At some point the doors and door frame were removed and returned to Jaguar Cars. For a couple of years these were installed in the Jaguar Museum at Browns Lane and now form a focal point in the display at the Collection Centre at the British Motor Museum at Gaydon.

2020 Daimler SP250 and SP252

in Front of the Foleshill Doors

in the Collection Centre

The Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust believe that Gardner and his team in the sawmill made the oak doors. They are definitely not standard factory made and it is obvious from the variations in the panels that these are a bespoke pair of doors.

Even without documentary evidence, we can be pretty certain that some of Fred Gardner’s work lives on in our Collection Centre.

Authors: Shihanki Elpitiya and Tony Merrygold

© Text and Images – Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust

Sources and Further Reading:

-

Parker, Chas and Porter, Philip, Jaguar C-Type: The Autobiography of XKC 051 (Porter Press International Ltd, 2017)

-

Grimsdale, Peter, High Performance: When Britain Ruled the Roads (Simon & Schuster UK, 2020)

-

Mennem, Patrick, Jaguar: An Illustrated History (The Crowood Press Ltd, 1991)

-

Whyte, Andrew, Jaguar: The Definitive History of a Great British Car (Patrick Stephens Limited, 1990)

-

Hull, Nick, Jaguar Design: A Story of Style (Porter Press International, 2015)

-

Porter, Philip, Jaguar: E-Type The Definitive History (Porter Press International, 2015)

-

Martin, Brian James, Jaguar: From the Shop Floor (Veloce Publishing Ltd, 2018)

-

Porter, Philip, Jaguar: Sports Racing Cars (Bay View Books, 1995)

-

Skilleter, Paul, Norman Dewis of Jaguar: Developing the Legend (PJ Publishing Ltd, 2017)

-

Porter, Philip and Skilleter, Paul, Sir William Lyons: The Official Biography (Haynes Publishing, 2001)

-

Porter, Philip, The Most Famous Car in the World: The Story of the First E-type Jaguar (Cassell, 2000)