William Lyons

Jaguar’s Founder

If you don’t have time to read this whole article than it is worth watching this interview from the Thames Televisions motoring show ‘Drive In’. Tony Bastable spoke to Sir William about the early days of the company. The interview was first shown on 18 May 1977.

Two particular points of interest leap out from this interview:

- Sir William was retired when this was made – but no mention of this – he still looks and sounds as if he runs the Company.

- He answers the question that is regularly asked about what SS actually stands for – ‘derived from Standard Swallow but we called it the ‘Swallow Special’.

1920 William Lyons

on a Harley Davidson

Introduction

William Lyons took a small sidecar manufacturing business and developed it into a prominent World-wide Company in a few years.

One of the few ‘names’ that still resound in the world of automotive manufacturing is that of William Lyons. We know Ford, Renault, Citroen and Benz, as these names are still to be found in the car business. Other once famous names, such as Olds, Riley, Austin and Morris have disappeared.

Very few people now remember who those pioneers were, but Lyons is still remembered as Jaguar; these two are synonymous. Although he died in 1985 his legacy is still regarded highly by the current Design Department at Jaguar. Indeed, Ian Callum, Director of Design from 1999 to 2019, often looked at past Jaguar models to keep the ‘Lyons-Jaguar DNA’ alive.

How did Lyons exert such an influence on a brand? He was a charismatic person, single-minded and certainly strong-willed. Tremendously hard-working Lyons expected his staff to do likewise. He surrounded himself with exceptionally talented people who were just as keen on the enterprise as he was.

They may not always have agreed with the Boss, but they were loyal, both to Lyons and to Jaguar.

Early Days

26 Oxford Road Blackpool (2022)

In any account of a life one must start at the beginning. William Lyons was born on 4 September 1901 to William and Mary (née Barcroft) who lived at 26 Oxford Road, Blackpool. William Senior was a musician and ran a ‘Music and Pianoforte Warehouse’ in Bank Hey Street where he sold and repaired pianos. According to some, most of the pianos in Blackpool passed through William’s hands at some time or another.

William Lyons attended Poulton-le-Fylde Grammar School where he was, in his own words, an ‘average scholar’, By 1911 his parents business was doing well and they moved to Red Cottage in Newton Drive, close to what would later become Stanley Park, and they had enough money to send William to Arnold House, a small private school in Lytham Road, Blackpool. Lyons may have lacked scholastic skills but from an early age he showed an interest in mechanical items, particularly bicycles, which he used to repair for other boys at the school, but his real interest was in motor cycles and their engines.

He was too young to ride but knew some of the older brothers of his classmates who had motor cycles. One of those whom he knew, Arnold Breakell, went off to war in 1914 and, unlike many others from school, returned home. He sold Lyons his 1911 Triumph motor cycle, even though Lyons was still too young to take the bike out on a public road. So Lyons pulled it apart and rebuilt it making some improvements; later he sold it at a profit. Lyons did have a natural talent for engineering of this type but the masters at Arnold House did not care for this talent and failed to encourage it and the headteacher Mr Frank Pennington told Lyons ‘he would never get anywhere messing about with engines.’

On leaving school in July 1917 Lyons was due to become an apprentice at Vickers shipbuilding yard at Barrow-in-Furness, he had attended a special course to help him with the apprenticeship examination, but his heart was not in shipbuilding and he was not keen to follow that path. His father came to the rescue; he knew the Managing Director of Crossley Motors in Gorton, Manchester, and asked if there was a place for his son. The result was that young Lyons took up an apprenticeship with them. Part of the arrangement included studying engineering at Manchester Technical College some of the week. Lyons wanted to get closer to the Crossley cars but production at the time was concentrated on ambulances and lorries for the military.

Unhappy with this, he left Crossley and moved back to Blackpool, where he found work with Jackson Brothers and then Jack (John Edgar) Mallalieu offered him a sales job at his new dealership – Brown and Mallalieu. Here he learned more about motorcars than he had with Crossley; how they were made and how they worked. He also learned how to demonstrate a model to a prospective customer and, importantly, how to close a sale. World War One had ended and life in Britain was slowly getting back to normal. He was much happier in these surroundings of a busy garage with sales of new cars and workshops to keep them going. He also attended the first post-war motor show in London in 1919 where he helped on the Brown and Mallalieu stand. William Lyons was just eighteen-years-old and was now as experienced with motor cars as he was with motorcycles, but when a new General Manager, Charles Hayes, was appointed to oversee the expanding business, Lyons found many of his responsibilities taken away. He may have had the experience but his age was against him. Consequently, Lyons’s services were dispensed with and in 1920 he found himself unemployed.

To fill in the time he helped in his father’s music shop by repairing and re-tuning some of the pianos that were sent to their workshops, but he was determined to get back into the automotive world. Incidentally, to the end of his days Lyons retained an interest in pianos and if a problem arose with the family instrument, he would take it to pieces and rebuild it. His younger daughter Mary recalled that it was not always a success.

Sidecars and Swallows

24 King Edward Avenue (2022)

Motor cycles were still a passion of William Lyons and he bought and sold several examples during the next few years, from Indians to Harley-Davidsons. He used to tune them for competition in local hill-climbs and rallies, which he sometimes won. However, he still did not have a proper job and his parents were getting concerned about his future, then fate took a hand.

He lived with his parents at 24 King Edward Avenue on the corner of Holmfield Road and then in April 1921 Thomas Walmsley retired from his coal merchant / haulage business in Stockport and moved into 23 King Edward Avenue with his wife and son William.

William Walmsley on SS80 Brough Superior motorcycle, and William Lyons in Swallow side car. King Edward Avenue, Blackpool 1923.

William Walmsley, who was some ten years’ older than Lyons and was also a motor cycle enthusiast, had built himself a sidecar to his own design and started making these in the garage behind number 23. Lyons saw this and got into conversation with Walmsley and introduced him to the Blackpool and Fylde Motor Club. Lyons was impressed by the sidecar and purchased an example; whenever he stopped his Harley-Davidson and the sidecar combination he attracted interest from passers-by and some expressed an interest in buying an example of this stylish sidecar for themselves.

While living in Stockport, Walmsley had designed and built an unusual sidecar using polished aluminium panels making it look far more stylish than the standard fare of the day. His sidecar had a sleek body with a pointed nose while the average ‘chair’ of the time was staid and rather boring. Walmsley finished the sidecar in 1920 and found that it was widely admired, this resulted in requests by fellow enthusiasts for just such a sidecar. Walmsley had started small-scale production with a couple of friends, in his garage in Stockport and continued after the move to Blackpool, at the rate of one a week. He sold the aluminium sidecars under the name ‘Swallow’ at £28 each, and another £4 would buy a hood, screen, lamp and aluminium wheel disc. Walmsley registered the design and had a photographic postcard printed with details of the Swallow. Initially his sister, Winifred, but later his wife, Emily, trimmed the sidecars which were built on a bought-in Watsonian chassis.

Swallow Sidecar’s First Factory

5 Bloomfield Road, Blackpool

With no advertising the sidecar was being ordered by people who simply saw an example in the street and Walmsley seemed content to indulge in what he regarded as a hobby and did nothing further to promote the product. On the other hand Lyons could see that the Swallow had great potential if it was marketed correctly. He suggested a business partnership with Walmsley, but the older man was reluctant to do so; he had no need to work and did not have the drive that Lyons possessed. Lyons did not give up and discussed the matter with Walmsley’s father who was more receptive and talked his son into the scheme, leaving Lyons to sort out the business plan.

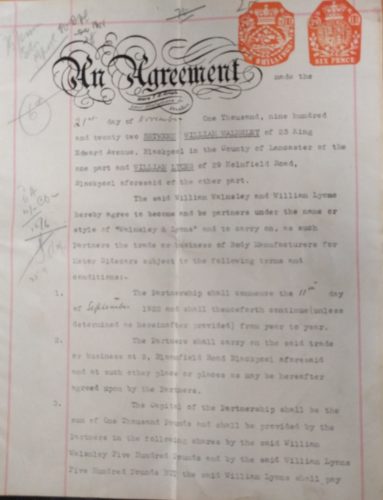

Lyons Walmsley Partnership Contract

dated 11 September 1922

In August 1922, William Lyons senior and Thomas Walmsley put up £500 each to fund the enterprise by guaranteeing a £1,000 loan (roughly £30,000 in 2018 terms) at Williams Deacon’s Bank in Blackpool.

They found suitable premises at 5 Bloomfield Road and the partnership agreement was signed on 21 November though it was backdated to 11 September 1922. Interestingly, the name ‘Swallow’ is not mentioned on any of the surviving documents from this time, but from the very start they traded as the Swallow Sidecar Company.

Early Days

William Lyons and William Walmsley, with half-a-dozen employees, began in a small way initially producing just one motorcycle sidecar a week, but fairly quickly increasing to the ten per week in the business plan. Lyons was not involved in the actual hands-on manufacturing, he attended to the paperwork, publicity and administration while Walmsley supervised the manufacturing aspect, after all, it was he who had designed and made the original. This was a suitable division of management duties that worked well, and production increased as further orders were placed locally for the Swallow.

Lyons wanted to introduce the Swallow to a wider market and that meant London, unfortunately, the date for space at the Motor Cycle Show in London that November had to have been booked by April, and when Lyons approached the organisers he was told that the Show was fully-booked. Lyons was not to be deterred and pleaded with them to be allocated a stand. Even though the entry date had long passed, and the Hall fully booked, the organisers agreed to allow Swallow space if any became available. Fortunately, a last-minute cancellation gave them a small stand and the opportunity to display the sidecar to a major audience in the capital.

The appearance of the Swallow sidecar at the London Show that year brought it to a wider audience and more orders were placed, though not as many as Lyons would have liked. The modern lines of the Swallow appealed to the public and for the following year more models were added to the line-up and additional staff taken on to cope with production. Some of these early workers at Swallow would stay with the Company right through the moves to Foleshill and later to Browns Lane until they retired. Though he was extremely busy and working all hours, William Lyons also found time to get married, to Greta Brown, on 15 September 1924; it was to prove a long and happy marriage.

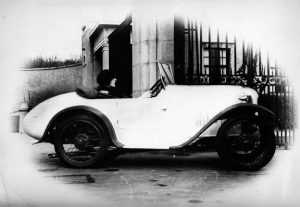

Swallow build Cars

In the early 1920s the emergence of cheaper mass-produced small cars provided very real competition for the traditional motorcycle and sidecar combination. Lyons himself had bought an early Austin Seven and was impressed by the simple and straightforward mechanics; he thought it could be improved upon but did not immediately set about doing anything about it. Meanwhile, he spotted a two-seater Austin Seven that had been re-bodied in fabric by racing driver Gordon England. This body was far more rounded than the pram-like original and set Lyons’s mind on track for his own version of such a car.

Swallow Sidecars were selling well but there was a gap in the market that Lyons had identified. The basic Austin and Morris models for around £150 were just that, basic and nondescript. He envisaged a slightly up-market variant that would give the owner an identifiably different car from others on the market. About the same time, William Walmsley’s father had sold his business and was looking for something suitable to invest some of the proceeds. He bought a property in Cocker Street, Blackpool and rented it to the Swallow Sidecar Company. It made good sense, as they needed more space to accommodate the expanding business. Swallow moved from the confines of Bloomfield Road in 1926.

The additional workspace encouraged Lyons with the car body venture; Swallow already had experience with body repair and trim, so it was a logical step. With increased space available, Swallow also took on bodywork repairs and car trimming. Lyons was keen to expand this side of the business and to justify the new sign – Swallow Side Car & Coach Building Co – on the outside of the building. One must assume that while Walmsley had drawn up and produced the sidecar that first caught Lyons’s eye, the design of subsequent sidecars were mainly from Lyons. He probably made a rough sketch that was translated by the experienced panel makers in the factory, but to design a full size car…

An advertisement was placed with several newspapers published in Coventry, Birmingham and Wolverhampton – the very centre of the motor industry – for a skilled worker with jig-making and panelling experience. Here Lyons was fortunate with the very first applicant to the advertisement. A former apprentice of the Lanchester Motor Company and one who had worked for Morris and others was interviewed. Cyril Holland seemed ideal and was capable of taking a simple sketch and then producing the jigs and panels necessary to execute the job. Holland was hired on the spot and asked how soon he could start. He had to give his employers – Mead and Deakin – a week’s notice so that was not a problem.

First Example

Lyons was further encouraged with his idea for a Swallow car in late 1926, when a Talbot-Darracq racing car that had been rolled on Southport Sands came was sent to Swallow to have a new body fitted. Holland worked on the Talbot-Darracq and when that had been completed he turned his attention to car design and one day was making a rough sketch for an open two-seat car with a rounded nose and tail with a ‘Vee’ windscreen. Lyons saw this sketch and asked for it to be worked out as a proper drawing to fit an Austin Seven chassis. He also made suggestions for alterations to Holland’s sketch. One must assume that Lyons and Holland had discussed the possibility of such work at the original interview or when the Talbot-Darracq was being rebuilt. The details are unclear and the above comes from later recollections by Holland and Lyons, as told to Jaguar historian, the late Andrew Whyte in the 1960s.

The next challenge was to obtain an Austin Seven chassis and Lyons contacted Stanley Parker in Bolton to try and buy an example, but Parker, as an Austin dealer, was concerned that he could lose his agency. (Parker also sold the Swallow sidecar and in later years would become a major SS Cars and Jaguar dealer, a partnership that lasted until the 1970s.) Parker agreed to supply the chassis on the understanding that he would be allocated the northern sales concession for the new Swallow-bodied cars. A chassis was duly delivered at the cost of £114.

This chassis was given to Holland. He had an uncanny ability to understand exactly what Lyons had in mind and, working from a rough outline sketch, would bring Lyons’ design to reality. Holland made the necessary working drawings from which Musgrove and Green in Birmingham were to produce the required aluminium panels. According to Lyons, he was not entirely happy with the general aspect of the first Swallow-bodied Austin, but admitted that it was more his fault than Holland’s. However, the round-tailed two-seater Austin looked good; it also had a rounded radiator shell that echoed the tail, and flowing lines which were quite a contrast with the normal upright Austin Seven body.

Andrew Whyte was able to speak to several of those involved with the original Austin-Swallow and later wrote: ‘The car had a drooping, long (and) vulnerable tail. The wire-mesh radiator guard bore the Austin ‘scroll’, on its own. There was a hole near the bottom of the guard which took the starting handle – the standard Austin handle, painfully hacksawn-through and an extension piece welded in! The ‘bench’ seat seems to have been a feature of this first car.’

Upholstery was real leather and the optional hard-top (£10) had a Bedford cord lining and an oval Celluloid rear window. The first version of the hard top roof was not a success; it was hinged at the rear of the body and lifted to gain access to the car, then lowered and secured via spring clips to the windscreen once the driver and passenger were seated. However, during an early test drive by Lyons the hood detached itself from the clips and snapped open, damaging the rear of the car. The design was worked on and the roof remodelled with two bolts at the rear and by snap fittings on top of the windscreen. It could be removed in a few minutes and the folding hood fitted in its place to make it a convertible for open-air motoring.

The prototype was registered FR 7995, but no photographs of it have survived; many years later a drawing was made from descriptions given by those who had seen and worked on the car. Quite different from the original Austin Seven was the inclusion of a better-equipped instrument fascia in wood – the original Austin was rather sparse in this area. Lyons wanted the Austin-Swallow to stand out and, apart from the better equipped interior, he had the cars painted in bright two-tone colour schemes – initially cream and crimson lake, but later suede grey and green – to set off the lines to great effect. There were other detail changes made to the original, for example on the Austin Seven the headlamps and sidelamps were combined and fitted on the scuttle. Lyons mounted his headlamps conventionally beside the radiator shell and individual sidelamps were set on top of the Austin cycle-type front wings. With subtle alterations and some neat design features, Lyons had achieved an expensive, individual looking car that would stand out but cost very little more than the basic original. His profit per car was small, but it would give him a foothold in the coach-building business and the motor car trade. The first Austin-Swallow was the start of a fruitful working partnership between the two men. Lyons would supply the most rudimentary of drawings for Holland to work his magic upon. Between them they produced some of the most elegant and stylish car bodies to emerge from any manufacturer. Mechanically the Austin Seven remained unchanged.

Swallow on Sale

Swallows outside Cocker Street

Following careful scrutiny and trials by Lyons and others at Cocker Street, the Austin-Swallow body was put into production and announced to the motoring press on 20 May 1927. It was priced at £175, which made it highly competitive with other special-bodied Austin Sevens then also on offer. Lyons kept his promise to Parkers, in return for the chassis, and gave them the northern distributorship for Swallow-bodied cars. He also visited Brown and Mallalieu in Blackpool, for whom Lyons had once worked, to sign them up for the new Austin Swallow.

While Alice Fenton handled sales of most of the Sidecars, including a sale to Nottingham Police, Lyons was free to put his efforts into selling Swallow cars further afield, arranging an appointment with his sidecar dealer in Birmingham, Frank Hallam. Hallam didn’t keep the appointment so Lyons instead went along to P. J. Evans who placed an order for 50 cars in return for which Lyons also gave Evans exclusive distribution rights for Swallow cars over a large area of the Midlands (Evans too was to become a major Jaguar dealer). Hallam’s alleged visit to the local pub meant he missed out on the opportunity of a lifetime.

While these sales were vital to the small Blackpool manufacturer, Lyons knew he had to enlarge the sales area and this meant London and the South. With such a small staff, it would seem that Lyons did all the sales negotiating and dealer visiting, there appears to be no record of others, such as William Walmsley, going out on the road to sell the new car.

He contacted his former Brown and Mallalieu colleague, Charles Hayes, who was now working for H. G. Henly & Company in London about the Austin-Swallow. Though there had been a difference of opinion in the past between Lyons and Hayes, neither man held a grudge and Hayes was enthusiastic enough about the new Swallow car to arrange a meeting at Henlys in Great Portland Street. Lyons drove an Austin-Swallow from Blackpool to London in order to show it to Herbert ‘Bertie’ Henly and his business partner Frank Hough. He hoped there would be some interest and a small order might come out of the meeting. What he was certainly not expecting was Hough’s statement that they liked the model so much that they would place a direct order with Austin Motors for 500 chassis to be delivered to Swallow for the production of 20 cars a week for Henlys.

In Production

Henlys Limited may only have been in business for a mere ten years, but in that time they had established a major dealership for several marques including Austin. They had the necessary authority to place such an order and they had the outlets. What they required from Lyons was exclusive distribution rights to appoint their own dealers across a large area of the south of England and a steady supply of cars. They also intended to back their order with extensive advertising, something that Lyons simply could not afford to do on the scale Henlys were proposing. What concerned Lyons was fulfilling the production of twenty cars a week just for Henlys, let alone the orders from others, as Swallow was only just managing five cars a week at the time (increased to twelve a week, later in 1928). Lyons pondered the problem as he drove back to Blackpool to break the news to Walmsley and Holland. All he had as proof of the deal were the firm handshakes of Henly and Hough, no written agreement had been signed as yet; the contract would be signed on 1 January 1928.

With an order of such magnitude, Lyons was confident in enlarging the workforce and set about expanding the business. Holland rose to the challenge and sought methods of increasing production. Additional workers were hired, many from the Midlands and production began to rise; orders for Parkers and others had to be filled before that of Henlys. Their first Austin-Swallow two-seater was delivered, as agreed, on 21 January 1928. As one of the major dealers in the country, Henlys were ideally placed to extol the virtues of the Swallow. Their advertising assisted enormously in establishing the Swallow name; Lyons never forgot Henly’s support for the fledgling business and the two men remained friends until Henly’s death in 1973.

The Henlys’ order made life tricky for the small Blackpool works as they were unable to accommodate the chassis that arrived in batches of fifty from Austin. Lyons recalled that sometimes they were hooked together in fives and towed behind another car from the railway yard to the factory. Not an easy task and chassis were often lined-up all around the Cocker Street premises waiting their turn on the production line. The cars may have become a major part of the Swallow business but sidecars were also in demand – at 150 a week – and the production of both types, as well as developing a four-seater Austin-Swallow saloon for Henlys, meant that the Cocker Street factory became too small and another move was indicated. Lyons and Walmsley discussed the matter and they came to the conclusion – Lyons more than Walmsley – that Blackpool was too far from the centre of the British car industry in the Midlands, where many of Swallow’s suppliers were based, and the most prudent plan would be to move to the Midlands.

Lyons Moves to Coventry

Queens Hotel, Hertford Street c.1938

(Coventry Pub History Website)

Walmsley made several journeys to search for a suitable site in the Midlands and at one stage thought Wolverhampton would suit Swallow. Then fate took a hand and Lyons, when staying at the Queen’s Hotel in Coventry, met Mr Aylesbury of the Midland Bent Timber Company. During their chat Lyons mentioned his quest and Aylesbury introduced him to Charles Odell, who was a Coventry estate agent. Odell gave Lyons details of various factory buildings that were for sale, not to let, which was what Swallow would have preferred with their limited finances. However, among the factory sites that Odell suggested was a property owned by the Whitmore Park Estate Company in the Foleshill district of Coventry. Lyons was encouraged by Aylesbury to contact Noël Gillitt, who was the solicitor for the Whitmore Park Estates; this Lyons did and expressed an interest in the property on offer. On the day that followed, Lyons was taken by Gillitt to the site off Holbrook Lane, so that he could see what was available. There were four double blocks that had been completed early in World War One by the Government as reserve shell-filling factories; each block had eight shops of 5,000 sq.ft. (464 sq. m.) each and each building was much larger than the Blackpool factory. Two of the blocks were occupied by Holbrook bodies that made bodies for Hillman cars but the other two were empty. Lyons thought the third block would suit Swallow even though it had been left untended since 1919.

The next stage was to convince the Whitmore Park Estate board to make an exception and lease, not sell, the block to Swallow. A meeting was arranged between William Lyons and the Board, which was headed by George Gray, and Lyons explained what his Company did and why he wanted to move to Coventry and advance his Company. From the onset he was honest with Gray and his fellow directors by advising them that he could not commit Swallow finances to buy the block but asked for a lease with an option to purchase. Gray and the Board retired to consider the proposal and it would seem that they were impressed by the 28-year-old Lyons, as on their return they offered to make an exception in his case and lease the property. Lyons signed for the block for three years at a rent of £1,200 (about £48,000+ in 2018) per annum with an option to purchase the freehold at a later date. Lyons was delighted and telephoned the news to Walmsley before taking Noël Gillitt to dinner. This too was fortuitous, as Gillitt was married into the Rover family and knew the Coventry motor scene in some depth. Gillitt was very useful and he later joined the Swallow Board of Directors, a post he held until after the cessation of World War. Lyons and Walmsley made several journeys from Blackpool to Coventry before they could sanction the move to a rather run-down building. A local builder quoted £800 (roughly £32,000 in 2018) to clean and whitewash the building; this was rejected and Lyons asked Walmsley to take over the task using local labour. In 1928 the country was still in a depressed state and unemployment was high; Walmsley approached the local labour exchange, who promised to send twelve men the next morning. Imagine Lyons’s surprise when 50 men turned up for the job; he interviewed each man, using an Austin spare parts box as desk, and selected those who showed promise, one of them was a Mr Chandler who became foreman and was hired full-time, the others were hired for the duration of the work. Chandler was excellent and organised the work-force to complete the work in good time, he also supervised various minor building alterations to make the factory ready for the move. On 8 October 1928, Lyons and Walmsley signed the lease for the block in Holbrook Lane and committed themselves to whatever lay ahead for them in the motor industry.

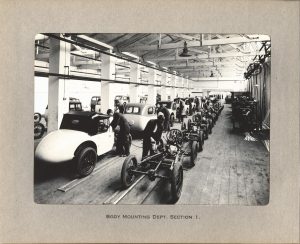

Austin Seven Swallow production at the Foleshill factory in Coventry

Only about 30 Swallow employees agreed to move from Blackpool, some of them had come from the Midlands so they were happy to return ‘home’, others were content to stay and find alternative employment in the North. One of those who did not want to move was Cyril Holland (see above) and this was a great disappointment to Lyons as he depended a great deal on Holland, but he knew that to survive Swallow had to make the move, which took place between September and October 1928. To ensure that production could continue with a minimum of delay, complete but dismantled car and sidecar components were packed ready to be assembled and within two weeks of moving completed vehicles were being moved to the despatch department ready for onward delivery.

Coventry was quite different from Blackpool and it was not plain sailing at first. There were problems between some of the locally-hired workforce and those who had come from Blackpool but eventually they all settled down. The Company faced another problem with production of the wood frames for Swallow bodies, which they built-up individually. Mr Aylesbury enters the scene once more at this stage when he suggested a new method of build to Lyons; this was to use machines that were tailor-made to cut all the frame components in quantity which would then be assembled in a dedicated jig. In this manner the sections could be stockpiled and used as required, making each body frame identical and saving time. Aylesbury’s company had patented a method of steam-bending curved components, another material and time-saver. Lyons was convinced and ordered the new machines; he also hired Frank Etches, who knew the steam process, to produce the curved sections. This did not go to plan as the resulting sections would not fit into the jig and when left the bent timbers would unbend. Etches tried hard but could not get the process right and one weekend he left, never to return. Swallow had orders to fulfil and production was in danger of coming to a standstill. Lyons wanted to maintain the jig method and, remembering how efficient Cyril Holland had been at Blackpool, coaxed him down to Foleshill, at a greatly increased salary, to sort out the matter. Within a few weeks Holland had ditched the steam-bending timber process, replacing it with parts made up from composite pieces and had the jig assembly process working correctly. Efficiency was greatly increased with a single team of frame-makers producing one frame an hour, reducing build costs. Production of the two Austin Swallow models – two seater and saloon – rose to 40 or more a week. Holland stayed with the Company and once again became the man who interpreted Lyons’s ideas for future models; he stayed with Jaguar until the end of World War Two.

Expanding the Range

With car production on schedule and further orders for the stylish Austin, Swallow was in a stable financial position and the two partners were able to purchase the factory block from the Whitmore Park Estates. On 29 September 1929, they bought their building and also the empty fourth block that adjoined the Swallow works paying £18,000 (about £750,000 in today’s values) (a mortgage was taken out with the Coventry Permanent Building Society) for the two. More space enabled the business to expand and with it the range also expanded; bespoke bodies were made for Fiat, Standard and Swift P chassis. Lyons boxed clever by using the same body style, with suitable size alterations, on different chassis. This was a further time and money saver and gave the customer a better choice of machine; Henlys often suggested a marque chassis to Lyons, they also continued to promote the Swallow in various publications and at their London showrooms in Piccadilly and on Euston Road.

Mention of Standard reminds us that for this model Lyons designed (with Holland’s help) a different radiator grille and it also brought him into contact with Standard’s Managing Director John Black. There were two Swallow – Standard models, the four-cylinder 9 in 1927 and the six-cylinder 16 (actually 15 hp) in May 1931, the latter being the last Swallow design. Another six-cylinder Swallow that appeared in April 1930 was the Wolseley Hornet-Swallow. This quite different looking model was available as a two-seater and (later) a saloon. By 1931, Lyons was concerned that sales were slowing of the Austin-Swallow models; no further supplies were available of the Fiat 509A chassis and the Swift Motor Car Company ceased trading. To keep Swallow in business he had to find an alternative and he was about to realise his dream of making a complete car to his own design and not simply a re-bodying of an existing chassis.

By 1931, the Swallow name was reasonably well known and William Lyons could see that the Austin Seven-Swallow, introduced in 1927 and still in production, could not be developed further. He may have stretched the Swallow body to accommodate the Standard Sixteen chassis, but there was nowhere else to take the design. The time was right to produce an original model. Lyons was encouraged in this venture by the General Manager of Standard Motors, John Black. Lyons discussed the matter with him and an agreement was reached where Standard would build-up a chassis and deliver it as a running unit to Swallow. Their part would be the design of this chassis and having it cast as a model for Standard. Lyons and Cyril Holland now began work on the chassis details; they were not draughtsmen but used their experience gained on the various Swallow models.

A wood pattern of the chassis was produced by the sawmill and given to Rubery-Owen, another Swallow supplier, to be manufactured in metal. Allan Crouch in his excellent volume on the SS I and SS II cars writes: ‘Although it appears that a prototype chassis was mocked up in wood by Swallow, the detail design was done by Standard, as Swallow did not yet possess its own drawing office. Its principal features were the double-dropped frame, made by Rubery-Owen, sweeping down between the axles, and the re-positioning of the spring hangers to lower the suspension.’

William Lyons was fortunate to be dealing with Black and Alfred Owen, who were both interested in the project and gave Swallow valuable advice and technical assistance. During 1931, John Black agreed to produce exclusively for Swallow a specific chassis that would take the Standard 16 hp six-cylinder engine and ‘another model incorporating the major units of our “Little Nine.”’ (This referred to the four-cylinder chassis and engine that was to be used for the smaller SS II also introduced in 1932). Standard was to provide the six-cylinder chassis solely for Swallow until the end of August 1932 and asked for a contribution of £500 ‘towards the cost of dies and tools for the production of the chassis frame.’ Swallow had to agree to take 500 of the 16 hp chassis at £130 each between October 1931 and 31 August 1932, and a ‘quantity to be agreed’ of the “Little Nine” chassis at £82 each. Should either party wish to cancel the agreement, it had to be done in writing and six months’ notice was required.

For the new venture, Reginald Maudslay (Chairman of Standard), Black and Lyons came up with “S.S.” as a trading name, quite what the initials stood for – if anything – has never been made clear. ‘Standard-Swallow’ has often been suggested but there is no confirming evidence and Lyons never referred to SS as such. However, Lyons did admire the Brough Superior SS80 motor cycle which he used to ride, perhaps he thought about the initials as a tribute, but all attempts to solve the mystery of “SS” have failed.

Lyons now had a chassis, what he now needed was a body to go with it. He had his own ideas of what the first Swallow-designed car should look like – it had to be sleek, low-slung and look fast – but he also contacted Black and Frank Hough of Henlys to discuss the design. Lyons listened to what they and others had to say and then went his own way, but with a better idea of what was required. He needed the assurance that Henlys and other dealers would take on the new Swallow model which would establish Lyons and Walmsley as car manufacturers.

William Lyons produced a rough sketch of what he had in mind and Donald Reesby of the Iliffe Publishing studios (he is also credited with the hexagonal ‘SS’ motif) translated this into a finished colour sketch. If the resulting drawing was made into a full-size car it would be some 18 ft (5.5 m) long, but it was a starting point and Lyons used it to work with Holland on design details. A wheelbase of 9 ft 4 in (2,845 mm) was chosen and with the spring hangers re-positioned to lower the suspension; the engine was set back in the frame. With sweeping bodywork, Lyons had his sleek model. He cleverly used close-fitting mudguards around the front and rear wheels and deleted the then obligatory running-boards. This immediately emphasised the long bonnet and gave the impression of harnessed power.

At the Swallow works a mock-up took shape using the Lyons preferred method of fixing panels (provided by Motor Panels) to a wooden buck and redesigning by eye as required. However, his work on the car was cut short when he was taken to hospital to have an appendectomy. In his absence, William Walmsley took it upon himself to alter the design. He made several adjustments, but the major modification was in raising the roofline to improve access and visibility. On the Lyons original, access and exit for driver and passenger was difficult and the actual driving position impractical.

On his return to the factory, Lyons was horrified when he saw the car and remarked that the roof looked “like a conning tower” and was not at all what he wanted; but he later had to agree that his business partner was correct to raise the roof to make it practical. Although it spoiled the lines of the car there was no alternative – as the London Motor Show at Olympia was less than a month away – but to keep the design. Meanwhile, The Autocar magazine had already published a news item in their 31 July 1931 issue announcing the fact that Swallow were to produce a new model known as the S.S. ‘The car is a marvellously low-built two-seater coupé of most modern line’ it enthused. ‘Aft of the long bonnet is a very smart two-door body, and at the back of the body is fitted a big luggage box.’ The note went on to add: ‘The S.S. frame is downswept in the centre, the engine mounted well back, the springs are rearranged to drop the frame as a whole considerably lower, and the wheelbase is lengthened. A special type of deep-chested radiator will be fitted, and the gear control will consist of a short lever mounted well back and close to the driver’s hand.’

1931 The ‘SS’ is Coming

This news item, which would have come from the factory, and a Swallow advertisement that was headed ‘WAIT! The SS is coming’ meant that Swallow/SS were honour bound to show their new car at the 1931 Motor Show. Work to complete the car in time for the Show went on day and night, there were problems to be overcome amongst them was the fabric covering for the roof. This gave the most trouble and the first attempts ended up looking frightful, so an expert trimmer, Percy Leeson, was brought in. He was excellent at his work and was able to complete the task overnight and the result was exactly what was required. Lyons was impressed with Leeson’s expertise and offered him a job with Swallow/SS; Leeson accepted and stayed with the Company and eventually became responsible for the trim shop until he retired from Jaguar in the 1970s.

Before the SS I made its debut at the Motor Show, Lyons wanted to bring it to a wider audience and sought the advice of Frank Hough. He suggested showing the prototype to Harold Pemberton, the motoring correspondent of the influential Daily Express newspaper. Pemberton visited Foleshill on 8 October and produced a lengthy article on the SS I that appeared in the newspaper the next day, a week before the Olympia launch. In the article, Pemberton called the SS I the car with the ‘£1,000 look’. He enthused about the car’s appearance: ‘The new motor-car is certainly the lowest-built British car I have ever seen. Two short people can shake hands over the top, and there is ample room within. It is so low that footboards have been done away with. With the sliding roof open, a short man can look down on the seats. The steering wheel comes below the level of the windscreen, so that vision is almost perfect. The car I saw was green externally, and the dashboard was of green wood beautifully engrained. The “S.S.” will certainly be one of the most novel cars on view at Olympia.’

Lyons owned a two-door Vauxhall Kingston at the time he was working on the SS I design and some style elements may have influenced him, for example the fabric-covered roof and external luggage trunk; these were features that appeared on the SS I. However, in this writer’s opinion, the SS I is the culmination of William Lyons’s design aspirations of making a new car to stand out from the more pedestrian models that were on offer. Certain design elements from the SS I would be developed by Lyons for SS and Jaguar in the coming years.

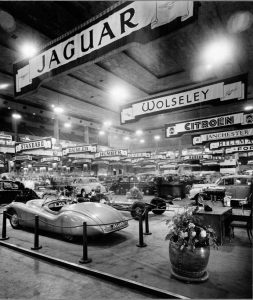

At the London Motor Show, Swallow was allocated space in the coachbuilders’ section and not in the main hall where all the established marques were. On the stand was the new carnation red and black painted SS I with a board proclaiming that it cost ‘£310 complete’. Sharing the stand was the smaller SS II coupé, a Wolseley-Swallow Hornet sports and an Austin-Swallow Seven. The SS I with its low body and a luggage trunk blended into the tail, large Lucas P170 headlamps and looking as if it was moving, even when stationary, was unlike any other car on show at Olympia that year.

For a ‘sports’ model that cost £310, the SS I was superbly appointed, with sycamore used on the fascia and excellent wood craftsmanship – a Swallow speciality – for the door cappings and the centre panels of the door casings. The door casings and the seats were trimmed with pleated Vaumol furniture-quality leather. Stepping into the new Coupé gave the owner a feeling that this was a car from an established up-market manufacturer. Lyons and Holland had worked their magic to make the interior an intimate and luxurious place to be. Like the Swallow saloons, the ladies were catered for with the inclusion of a Houbigant Ladies’ Companion vanity unit set into the lid of the glove box. Other cars of 1932, in the same price bracket, were less opulently appointed, and were not in the same league. To reach the same level of luxury as the SS I, one had to spend at least another £200. Perhaps those more costly models were better built and had more power, but none of them looked as good as the SS I.

Although the £310 SS I sported a 16 hp engine, for just £10 more one could buy the 20 hp version, but it was not so vigorously promoted. Production of the SS I and SS II went ahead at Foleshill and deliveries of the first examples of the two models reached dealers by the end of the year. Although the new model was well-received, sales for the first year were disappointing and only some 500 units were sold. The original SS I was produced for one year only; for 1933 Lyons designed and introduced a much-revised version. What introduction of the SS I did was to establish Lyons and Walmsley as independent motor manufacturers, not just as coachbuilders.

With the SS I Lyons had designed a new car that would carry the Company name into the mainstream of motor manufacturing. He took a calculated risk and produced a good-looking sports saloon at a very keen price – profits were small – but he knew that once SS was established it would lead to bigger and better models. How right he was. Just four years later he produced the first SS Jaguar range, which included the SS 100. William Lyons had a vision, he knew what he wanted and set out to make that vision come true.

Smaller Model

From the start, although the SS I made use of many Standard components, there was much that was dedicated only to the SS product, for example the specially designed chassis, but this would not be the case for the SS II. This model could, in effect, be seen as the last of the line which Swallow began with the re-bodying of Austin and other chassis. Initial examples of the SS II were constructed on the unmodified chassis of the Standard Little Nine including engine, gearbox and other mechanical elements. There were some changes made to the instrument layout, and the steering column and gear lever were both modified to suit the lower layout of the SS body, but generally the underpinnings were unchanged.

Cyril Holland and William Lyons adapted the SS I body to fit the unmodified Standard Little Nine chassis with a wheelbase of 91 inches (2,286 mm). What emerged was an elegant, scaled-down version of the SS I and one that was far more attractive than the original Little Nine. Because the bonnet of the SS II was not exaggerated – as on the SS I – the proportions of the smaller car are very pleasing. This makes it look more ‘normal’ than its bigger brother and possibly a little more in keeping with other cars of the time. However, while the SS II may have looked more pleasing aesthetically, it was always going to be in the shadow of the larger car’s superior performance.

One commentator has noted that the style of the SS II is in proportion, and only when one sees it alongside the SS I does one realise that it has a shorter bonnet, smaller headlamps and an ‘altogether daintier appearance’. While it looked good, it was small and rather cosy inside, but that was in 1931 when any car was a luxury. As with the SS I the smaller stablemate carried close-fitting helmet wings (no running boards), a compact passenger compartment and a separate luggage trunk. When the car was announced for sale in 1932 it carried a very reasonable price tag of £210 and represented exceptional value for money.

William Lyons’s father was an early owner of an example; he took delivery in May 1932 of chassis 300260 (KV 7920). William Lyons himself has three SS IIs registered to him variously between 1932-33 and Mrs Lyons owned chassis 300379 (KV 8460).

Although William Lyons had completely restyled the SS I for the 1933 season, he left the external appearance of the SS II unchanged, complete with helmet wings, to continue for another year. However, in October 1933, for the 1934 season, SS Cars announced new models across the range. Lyons had restyled both types and the SS II benefited by having its helmet wings deleted in favour of long flowing front wings which incorporated running boards.

The bonnet line was raised, the windscreen rake was increased and the rear window could be opened. Also, the front was further enhanced by a new chromium-plated radiator shell with vertical slats very similar to that of the SS I, although simpler in construction. Incorporated into the radiator shell was the one piece winged motif and surround that was fixed to the top centre of the radiator grille with a bold ‘SS II’ badge of silver letters on a black background identifying the model. A pair of Lucas LB/140/EDFE/5 headlamps, which gave a more concentrated light than the previous Lucas P140 lamps, was fitted. Stronger supports for the wings were an added feature of the revised chassis, and the headlamps could therefore be mounted on pods fixed to the stiffened wings rather than on struts fixed to the radiator as had been the case with the first SS II models. A new instrument panel, almost identical to that of the SS I was adopted; this was in pressed metal with raised hexagonal surrounds for each instrument. French walnut was used for the dashboard, fascia and door cappings.

While the SS I kept its original chassis the SS II received the chassis from the new Standard Ten (10 hp 1,343 cc) and Twelve (12 hp 1,608 cc); this chassis extended the wheelbase from 91 inches (2,286 mm) to 104 inches (2,642 mm) and the track was increased by eight inches. With the new chassis, Lyons was able to expand the body styles of the SS II; he produced an attractive Saloon and a Coupé that emulated closely the lines of the SS I. To keep matters simple, the Saloon (in both models) was the Coupé with a window installed instead of the dummy hood-irons and the fabric-covered rear section. The luggage trunk was given a smoother appearance with rounded edges and was better incorporated into the body, also the spare wheel was given a metal cover with a chrome band around its circumference. With more room in the cabin, separate front and rear seats replaced the bench seats of the older model. A neat touch was the inclusion of two small pull-down trays located in the side panels of the rear compartment. While they cannot be termed ‘picnic tables’ they would hold a glass, Thermos flask or a cup and saucer. The 1934 SS II was a true four-seater, five at a pinch, whereas the model it replaced was really a two/three seater at best. SS Cars had introduced a worthy small car into the catalogue and a very smart one at that. Prices were now £265 for the Saloon and £260 for the Coupé, with an additional £5 if the 12 hp engine was specified. At a stroke the revised designs totally changed the SS models for the new season and as the 1934 SS II shared many components with the SS I this must have made production somewhat easier in build and to budget for.

Open Top Introduced

With an extended range of saloons and coupés in the catalogue, Lyons turned his attentions to producing an open top model. At the 1933 London Motor Show the SS I Tourer was shown for the first time. Early the following year it was joined in the range by an SS II Tourer, which went into production in March at Foleshill. This design, based firmly on the saloon/coupé, but with an open body taking cues from the larger Tourer, shows Lyons at his best. The line flows effortlessly from the front wings to the rear without a break; the racing style was enhanced by the use of twin cowls on the scuttle, emulating the SS I Tourer and similar to the racing Rileys and MGs of the day. From the twin cowls on the scuttle, a neat continuous line led down to the cut-away doors and around the passenger tub.

Like the SS I Tourer, the hood was well made and folded away easily and neatly; the side-screens could be quickly detached and stowed in a special pocket. Considerable thought was given to the weather proofing of the open cars to make them even more attractive for potential customers. The cut-away doors gave the front seat passenger and driver more elbow room. Three hinges were fitted to keep the doors from sagging. Another noteworthy addition were internal door handles, not always found on cars of this type. The front of the SS II Tourer was the same in style as the Saloon and Coupé, and some examples carried the silver ‘SS’ letters on a badge with a red background.

As with the SS II Saloon and Coupé the SS II Tourer was a full four-seater, but unlike those models it was equipped with a slimmer luggage boot that, when the hood was folded down, was soon filled with the hood cover and sidescreens leaving little room for much more than a very small valise. The style of the boot was deliberate on both Tourer models; it was a particularly harmonious line that Lyons was aiming for that dictated the dimensions. Whatever the shortcomings may have been, when the hood is down the Tourers do have a flowing line, from the top of the bonnet right to the rear bumper and this is matched perfectly by the lower line from the very front of the wings to the trailing edge of the rear wings.

The Tourer bodies are very pleasing to the eye and show Lyons getting into his stride for the coming SS Jaguar and the SS 100, which would then lead, although interrupted by World War Two, right through to the XK120 and Mark VII. There is no doubting the excellent style and sporty appeal of both the SS I and SS II Tourers and Coupés, but it was the saloons that sold in greater numbers returning a healthy profit for SS Cars.

Lyons wanted to develop the Company further: S.S. Cars Limited was registered on 26 October 1933, with a capital of £10,000 in £1 shares and took over the manufacturing of the cars; Swallow continued with the sidecar business. From now on the main business was with SS Cars and the range was further extended with the arrival of a Saloon with extra windows instead of the dummy hood-irons of the fixed-head Coupé. During the following year SS Cars continued to develop and expand the range with a further modified SS I and a new SS II; the SS I Airline, which had been styled by Lyons and Holland, was also added to the catalogue. By the end of 1934, the Company was in a much better financial state than it had been for some time and sales of the range were on the increase. However, it was becoming apparent that while still popular, the days of the SS I and II were coming to a close. Besides which, Lyons already had plans for a new model range to replace both types in a spectacular manner. Production of the models was slowly wound-down with the last examples being built in September 1935.

Sales of the two SS models were good and though the margins were tight, Swallow could show around £15,000 profit in the bank by the end of 1932. This was opportune, as with the works busy – Swallow Sidecars were still very important and selling strongly – space was at a premium. Lyons wanted to expand and when the two blocks of four buildings next to Swallow, which had been occupied by Holbrook Bodies who had gone out of business, came up for sale, he made an offer, after some delay, of £8,000 (around £400,000 today) for the buildings. This was accepted and gave Swallow the extra space they required. Some sources quote £12,000 as the purchase price which included the Holbrook sawmill.

Lyons also brought in Howard Raymond Davies to market the sidecars. Davies was well-known in motorcycling circles as his company, HRD, built and raced motorcycles; Davies himself won the 1925 Senior TT with one of his own machines. He sold the HRD business in 1928 and, after a few years dealing in the bike market, joined Swallow. He certainly revived sidecar sales and made changes to the design and manufacture of the famous product. With Lyons’s agreement, a change of sidecar chassis supplier from Mills-Fulford to Grindlays of Coventry was made in 1935. A couple years before this the word ‘Sidecar’ was dropped from the Company’s title.

Walmsley Departs

William Walmsley and William Lyons had not seen eye-to-eye about the future of their Company for some time. Lyons could never understand why Walmsley was not interested in developing the marque and expanding the business, Walmsley simply did not have the drive that Lyons had. Also, Walmsley did not relish the pressure of running a successful car manufacturing company, he was content to let the business look after itself. Lyons in contrast was working all hours of the day and constantly looking at ways of keeping the factory busy with product. With the floatation of the Company Walmsley talked to Lyons about leaving Swallow/SS and retiring. Walmsley did not want any share-certificates as part of his settlement and this meant that Lyons had to buy Walmsley’s share of Swallow/SS. The sales of shares in SS Cars Ltd opened on 11 January 1934 and Lyons became Chairman and Managing Director. Walmsley left the business he helped create a wealthy man, and was determined to enjoy spending the funds on other interests. Lyons was not unhappy to see Walmsley go and as sole-owner could get on with the development of the brand.

Jaguar Emerges

Lyons had asked Harry Weslake, a man who could work wonders with existing engines, to develop the Standard unit to give more efficient power. Weslake designed a new overhead valve cylinder head for the unit and this was produced exclusively for SS by Standard. Having used the engine in the revised SS models, Lyons continued with the powerplant for his next design. This was a larger saloon which was designed in the Lyons-Holland manner with panels fitted and discarded as the model progressed. Working with Holland and Lyons was Fred Gardner, who ran the wood shop. He did more than that, as it was up to him to provide the wood styling buck and have the panels made that would be used to style the car in three-dimensional form. Lyons’s method of working was quite unorthodox when compared with other car designers of the day. As he could not draw, Lyons relied on Holland and Gardner to interpret any vague sketch he might make. After Holland left Jaguar it was Gardner who took over completely and worked with Lyons on Jaguar designs until both men retired. Gardner was a ‘character’ and would not allow anyone outside his department access to his work area, not even senior management, and he was known to throw tools at anyone who breached the security of his workshop. Gardner was the only person at Jaguar whom Lyons called by his Christian name, all others, as was the custom of the day, were referred to by their surnames.

SS Cars did not have a chief engineer and relied on Standard and Harry Weslake for any engineering advice or changes. Consequently, with the expansion of the business, Lyons decided the time had come for the position to be rectified. On 1 April 1935 he appointed 32-year-old William Munger Heynes to the post of Chief Engineer. It was an important decision and one that paid off handsomely over the years; Heynes came with a wealth of knowledge and a healthy respect within the industry. Lyons told him about the new car that was in design and left Heynes to work out the required engineering aspects while he and Holland got on with the body. Heynes immediately set about establishing a small drawing office and streamlining the outside supply chain. He made changes to the quality of material that was being bought. Though he was a latecomer in the progress of the new model he made a major contribution to making it a reality.

1935 Mayfair Hotel, London

SS Jaguar Launch

Holland took the existing radiator shell from a Bentley and re-styled it to suit the smaller four-door SS saloon and work progressed at Foleshill in building a prototype. As per usual Lyons used his own method of construction: full-size panels offered onto a wood frame and designed by eye with alternative panels changed as required. The car was ready for a trade showing at The Mayfair Hotel in London on 21 September 1935.

Known as the ‘SS Jaguar’ it was available with a 2.5-litre engine and shared the catalogue with a smaller 1.5-litre saloon and a two-seater SS Jaguar 100 sports, also with the 2.5-litre engine. The SS Jaguar was received with great acclaim and the gathered dealers were asked by Lyons to guess the price of the saloon, they offered around £600 as a guide price. Lyons amazed them by stating that the car would retail for £385 and would be available for sale in the new year.

William Lyons had spotted the gap in the market for a competitively-priced sports saloon and in his usual manner had filled that gap with a good-looking car at an excellent price. One should bear in mind that in 1935 few people owned a car of any sort and one that offered the luxury of the SS Jaguar may seem cheap today at £385 but the average weekly wage was about six pounds, so it was almost equal to a year’s salary. The new models were a success and brought the SS name to greater prominence, and in the years before World War Two the range was expanded. This success enabled SS Cars to grow and additional factory buildings were erected to Lyons’s own specifications; they were large, modern and built to manufacture cars. This made a change from the older buildings which had never been ideal for car production. However, with War declared in September 1939 the production of cars slowed down and by 1940 had stopped altogether. War work was vital and Lyons secured contracts to repair Armstrong Whitworth Whitley bombers and, more importantly, obtained contracts for a large number of various sidecars for the military.

During the war years the post-war market was not forgotten; it did not occur to many in Britain that Germany could win and accordingly plans were made for sales following the conflict. At Foleshill a group of fire watchers – who nightly kept a look out for enemy bombers – including William Heynes, Walter Hassan, Claude Baily and William Lyons, planned the future. Lyons had in mind a new large saloon and wanted a “good-looking” engine to power it. The group discussed the brief during those long hours and the outcome was the remarkable six-cylinder XK engine. It was powerful and looked good.

Enter the XK

After the war the saloon range was slightly modified and entered production, the SS 100 was discontinued and the name of the Company was changed from SS Cars to Jaguar Cars Limited. The proposed large saloon was taking time to develop and in its place Lyons quickly produced a stop-gap model which would go on sale as the Jaguar Mark V, still powered by the Standard-based engine.

He wanted to showcase the new XK engine and in a very short period of time, working with William Heynes and Fred Gardner, designed and built the XK 120. This was intended to be a limited production model and was shown at the first post-war London Motor Show at Earls Court in 1948. Because of the shortage of steel the first production Jaguar XK120s were aluminium bodied. William Lyons was still battling for a larger steel allocation, but had to convince the Ministry of Supply that Jaguar would be increasing their export sales. When the Americans saw the XK120 they ordered in quantity. However, production was very slow due to the steel problem, and there was a very great danger that the orders would be lost if Jaguar could not deliver.

XK120 Launch at the

1948 Earls Court Motor Show

Having got the Jaguar XK120 into limited production, Lyons concentrated on the saloon he had been working on for some years. In his usual manner of developing a new model, Lyons had panels made to his specification that were then offered up to a mocked-up pattern already in place. As usual he looked at the way the light fell on the curves of the car; using string, wood and metal rods he would fine-tune the shape until he was happy. With the Mark V he had blended the headlamps more into the wings, although they were still somewhat proud. With the new saloon the headlamps were moulded further into the body on either side of a new grille. The old bold radiator grille was made smoother in appearance, more in keeping with the emerging 1950s. During a sales tour to promote the XK 120 William Lyons had picked up on the mood of American customers and some of the comments made to him were remembered and incorporated into his new design.

Jaguar Competes

Meanwhile, the Jaguar name had to be kept in the news. Already the XK120 had captured the imagination of the public and left the opposition behind. Now, Lyons had to confirm the excellence of the car and the new engine. His chance came with the announcement that the British Racing Drivers’ Club would hold a Production Sports car Race, sponsored by the ‘Daily Express’ newspaper, at the former airfield at Silverstone in Northamptonshire in August 1949. Jaguar entered three XK120s, to be driven by Peter Walker, Leslie Johnson and Prince Bira, with the team to be managed by F R W ‘Lofty’ England. During a trial session Lyons drove one of the cars around the circuit. He had not lost his touch and set up a good speed. Johnson and Walker took first and second places. The new car and engine gained their first competition success.

By 1950 the new saloon was well advanced and being tested; Lyons had put the XK120 into full production and steel was becoming more generally available to the country. Lyons visited the Geneva Motor Show in March and later the New York Imported Car Show; Jaguar was prominent at both venues. Lyons was disappointed with the sales of the Mark V in the USA, but was cheered by the increased interest in the XK120. It was this model that he had to get shipped in quantity to meet the demand. Soon after his return from America, Lyons was elected President of the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMTT), an appointment that pleased him greatly. Becoming President of the SMTT was an endorsement of his standing in the motor industry and also the acknowledgement that Jaguar was indeed a major player.

Meanwhile, the works-prepared XK120s were being entered into some of the most gruelling competitions. In April, Leslie Johnson came fifth in the Mille Miglia, but in other events the cars failed to finish. Generally, they were let down by mechanical problems, which was not surprising as Jaguar had no recent experience with such competitions using fairly standard production cars.

However, Ian Appleyard and his wife Patricia, (née Lyons,) drove their white Jaguar XK120 (NUB120) to victory in the 1950 International Alpine Rally. That same year Stirling Moss drove Tommy Wisdom’s XK120 to victory at Dundrod and earned Lyons’s respect. He signed Moss up as a works driver on the spot and started Moss on his racing career.

It was Le Mans that Lyons wanted to conquer. With the XK120 and the superb XK engine he had the opportunity. The low-key entry of three cars in 1950 was a toe-in-the-water. They did not finish but encouraged Lyons to make a firm commitment to Le Mans for 1951.

New Model

Jaguar was exporting more than 80 per cent of their production, but they were still far down the list for steel allocation. Lyons continued to press for increased allowances and the Ministry of Supply finally rewarded his persistence. At the Motor Show in Earls Court that October was the new saloon, the Jaguar Mark VII. Another triumph for Lyons and Jaguar, the fresh looking silver-blue saloon was displayed on a backcloth of red and grabbed the attention of the crowd. Helping the image was the price tag of £998. Lyons had done it again; here was a luxury car, with wood, leather and deep-pile carpets, at an impressive price. Orders, from the UK and overseas dealers, were taken for delivery the following year. As soon as the Earls Court show closed the car was shipped to New York and shown at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel. Once again it created a sensation and more orders were added to the book. Lyons had used a few key details from the preceding Mark V, but the style of the Mark VII is quite different from anything that had been seen from Jaguar before.

It was also to bring Jaguar their first Royal Warrant; Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, purchased an example and in ensuing years purchased other Jaguar and Daimler cars for her use. Together with the XK120, the Mark VII placed the Company firmly in the post-war year headlines with a vengeance. All that was required was to keep up with demand for the products.

With the increase in production Lyons had sought to enlarge the Foleshill plant, but permission to do so was refused. He was offered alternative facilities elsewhere in the country but was adamant about staying in the Midlands area. During the build-up towards World War Two several new shadow factories had been commissioned and built. One such shadow factory was on a 62-acre (25 hectare) site at Browns Lane, Allesley near Coventry, and was built for Daimler Motors to manufacture Bristol Hercules aircraft engines. Following the cessation of the war the factory had not been run to capacity by Daimler and was ripe for Lyons to acquire. He did not have it all his own way and obstacles, mainly from Daimler, were put in his path, but he could prove a full order book that was predominantly for export. In the event an agreement was reached for Jaguar to rent the premises, and by November 1952 the Company was installed at Browns Lane.

Le Mans and Consolidation

Meanwhile, there was work to be done at Foleshill. In 1950, although it did not win, the XK120 had proved that it was equal to the gruelling 24-hour race at Le Mans. At the end of the year, Lyons gave the go-ahead for the building of a special racing model for 1951. Under the direction of Heynes, Bob Knight designed a tubular chassis to take a modified version of the 3.4-litre XK engine. Although beautiful the XK120 body was not ideal and had to be totally redesigned for Le Mans. This task was given to Malcolm Sayer, who had joined Jaguar in 1950. Sayer had worked at the Bristol Aeroplane Company and was an excellent engineer and aerodynamicist. So he was the ideal person to develop the car.

1951 Le Mans

Peter Walker

The emerging design was called the Jaguar XK120C (C for Competition), but soon became universally known as the C-Type. Three cars were entered and Lyons joined the team, under Jaguar race-manager F R W ‘Lofty’ England, at Le Mans. It was not an easy 24-hours for Lyons as he watched. Two cars failed to finish and he feared the worst, but the third car, driven by Peter Walker and Peter Whitehead, took first place and gave Jaguar their first Le Mans victory. Jaguar was even more in the limelight and confirmed Lyons’s belief in publicity brought by such victories. It was far better than any designed advertisement. The race win created even more demand for the cars and production had to be increased.

Once the Company were able to move in to Browns Lane, more time could be allocated to other matters. A fixed-head coupé XK120 was released. It was a good-looking car, with echoes of the one-off pre-war SS 100 Coupé, and sales continued to rise. Lyons was as busy as ever, promoting Jaguar and trying to keep the American dealer body on an even keel. There had been problems, and Lyons made a fortuitous appointment of Johannes Eerdmans as head of Jaguar Cars America. It was a new post and he would deal with the day-to-day organisation of the Jaguar dealer network in the USA. Meanwhile, Lyons was also at work on a small Jaguar saloon that was sorely needed in the range.

Heynes and his team had taken the C-Type apart and developed a new variant for the 1953 Le Mans. Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton took first place and Stirling Moss and Peter Walker second. Jaguar also set the record for the first ever 100 mph (160 km/hr) average for the race. Lyons was there to see this fabulous victory. The newspapers blazed the name Jaguar in banner headlines across the pages; on BBC radio the drama was relayed to people at home, and the cinema newsreel cameras brought the action on the big screen right into the heart of Britain. In the days before television sports coverage, these methods were the only way to reach a mass audience. Jaguar could do no wrong.

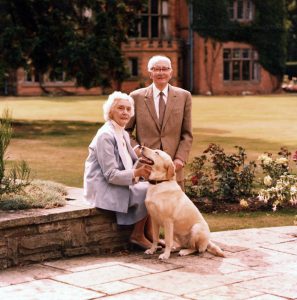

As an alternative to the car business, Lyons had started to farm in the immediate pre-war years and with an increase in income expanded this side of his interest, he would devote more time to farming after his retirement. Apart from the farm, Lyons also spent rare leisure time at a small house he had purchased in 1950 in Salcombe, Devon. It was these times away from the running of Jaguar that enabled Lyons to recharge his batteries. While he thrived on work he needed time to be with his family and friends and forget about the troubles of industry. Whether he ever forgot about Jaguar when he was away from the factory is unlikely. Although in a few short years the Company had taken a leading role in the motorcar business in the UK and established a thriving North American market – something that had eluded many longer established companies – Lyons was still at the helm and steering Jaguar with a very firm hand. He was involved with many facets of the motor business, and it was Jaguar and Lyons who co-operated with Dunlop to develop the use of disc brakes on production cars. They had been used on the C-Type and the value was seen in applying them to road cars. In 1954 the XK120 had been developed and, as the new XK140, it was unveiled at the Earls Court Motor Show. Lyons was still at work on the small saloon.

Family Loss

William and Greta Lyons suffered a personal tragedy when their son John was killed. He had been groomed to take over from his father and was working at Browns Lane. In June 1955 he was en route for Le Mans, driving a Jaguar Mark VII support car, when he collided head-on with a US military vehicle. John Lyons died instantaneously. His parents never got over the tragedy and William Lyons plunged himself deeper into his work. It was his way of coping. In private, he and Greta Lyons would have grieved, but in public, Lyons would not allow his emotions to take over. He had come up the hard way from Blackpool and that was his way of getting through life. John Lyons had established himself as a popular member of the Jaguar team, not because he was the boss’s son, he was genuinely liked and William Lyons would not have made concessions, you had to perform, no matter who you were, to stay at Jaguar.

Work on the new saloon was progressing slowly and it was not until October 1955 that the Jaguar 2.4-litre was unveiled. Like the XK140 and Mark VII, the new car was stylish and was Jaguar’s first unitary model. It looked fresh and priced at £1,269 – cheaper than the Daimler Conquest (£1,511) and slightly dearer than the Riley Pathfinder and Wolseley 6/90 (£1,205). These cars, along with the Rover 75 – at the same price – were the competition. Previously, Lyons had introduced small-engined versions of the larger models; here was a smaller car with its own version of the proven XK unit. There were key design cues taken from the XK120/140 and the Mark VII to show the family likeness, but it was unlike any previous Jaguar, hence the longer gestation.

Knighthood and Fire

William Lyons’s sterling work for the British motor industry was recognised and he was knighted in the 1956 New Year’s Honours List. He regarded the honour as one for Jaguar rather than for him personally. That year the upgraded Mark VIII was announced. It was a plusher Mark VII with better interior fittings and some external style alterations. Another accolade bestowed on Jaguar was the visit by HM The Queen and HRH Prince Philip to Browns Lane in March. They spent some time touring the factory and talking to people in management and on the factory floor. Business continued and the new 2.4-litre saloon was put into quantity production.

1957 Browns Lane Fire

All production was halted when a fire broke out in the factory on 12 February 1957. It was a tremendous blow several hundred cars – including the yet to be announced 3.4-litre small saloon – and a great deal of the factory were destroyed. Lyons and others who were still on the premises helped to push or drive cars out of harm’s way to safety, but the damage was considerable. Lyons rose to the occasion and spoke directly to his workers and his suppliers and they rallied round. Within thirty-six hours the factory was in limited operation and two weeks later production was under way, and the repairs were completed by early June.

The fire did not stop the launch of the 3.4-litre version of the small saloon the XK150. Lyons had improved the looks of the saloon by the fitting of a newly-designed wider grille that was more pleasing to the eye and in keeping with the XK150. After repeated success at Le Mans, Lyons had withdrawn the works team but worked closely with others, such as Ecurie Ecosse, in having cars prepared by the factory for race meetings. Jaguar exports were up, helped by the new saloon, and finances were in a healthier state than for many years. However, there was no time for standing still and progress was the order of the day. Although the 2.4/3.4 saloon had been successful there was room for improvement and Lyons was already developing it when the first cars arrived in the showrooms.

Greater Heights

William Lyons often listened to what was said about his cars by customers, dealers and the Press. He would check stories and facts and when a valid suggestion or criticism was made he would discuss it, sometimes, with his engineering team and act. Generally, he made his own mind up and once he had made a decision it was hard to make him change it. Those who worked with him have recalled that Lyons would sometimes have decided on a course of action before he entered into any sort of discussion about it. Especially, Lyons listened to the US dealers, he did not always agree with them, but – as the US market was the most important in terms of export sales – he listened. However, he was often let down or frustrated by labour problems and industrial disputes in the UK. These problems were not exclusive to Jaguar and seriously affected the British car industry. The all important export market was suffering and Jaguar with it. New models introduced included the upgraded Mark VIII in 1957 and the 3.8-litre Mark IX in 1958. This was the first Jaguar to have disc brakes and power-assisted steering as standard. The 3.8-litre XK engine had a new cylinder block and was not simply a 3.4-litre bored-out from 83 mm to 87 mm. Behind the scenes changes to the 2.4/3.4 saloon was being worked on, as were a small sports car and a large saloon.

In 1959 Lyons made a purchase offer of £1.25 million for the Browns Lane site and this was accepted by the Ministry of Supply. Meanwhile, the new Jaguar 2.4 and 3.4-litre saloon, known as the Mark II, were unveiled that year, as was a 3.8-litre version. The car had a brighter interior, achieved simply by replacing the upper door pressing with chromed frames for the windows; the front windscreen and rear window were also enlarged. The narrow rear track of the earlier car that had come in for adverse comment was improved by widening it from 50 ins (127 cms) to 53.4 ins (135 cms). This improved the handling of the car greatly, and with the rear being redesigned the saloon took on a more pleasing look. A slight facelift made the front of the car more in keeping with 1960 and greatly attracted the public.

Eventually, over 100,000 examples of the Jaguar Mark II were manufactured. It was a car that struck a chord across the car-buying public. The Jaguar Mark II became a firm favourite with people from all walks of life and also the Police, who used the model in various roles, from urban patrol to motorway work. It was also used by the Flying Squad, Special Branch and, unmarked, in the VIP protection role.

Expansion and Daimler