Experimental Engineering

XP/11 ‘The Light Alloy Car’ – The Missing Le Mans Link

Jaguar had won at Le Mans in 1951 but were not successful the following year, to address this they developed a quite different contender.

The success of the XK120, both on the road and on the track, encouraged chief engineer, William Heynes, to sanction a dedicated competition model. He entrusted the task of the body style to recently-arrived Malcolm Sayer, the engineering to Phil Weaver and the suspension and chassis to Bob Knight. These men and their dedicated teams quickly produced the XK120C – C for Competition – in time for the 1951 Le Mans 24-hours Race. Three cars were entered and the race was won in record time by Peter Whitehead and Peter Walker. The new model soon became known as the C-type and though its XK120 origins could be noted, it did look quite different from any Jaguar model of the time.

For the 1952 Le Mans 24-hours race Jaguar entered three C-types that had been modified for the race with streamlined nose and tail sections with a revised cooling system which included new pipes and hoses. They were not successful and severe over-heating put all three cars out of the race within the first few hours. This was humiliating for Jaguar after the win in 1951 and the Company was determined that they would do better in 1953.

Four C-types were entered for the 1953 race, the three works cars were equipped with the new disc brakes while the Belgian Ecurie Francorchamps car still had drum brakes. The C-types fared well and all four cars completed the course with Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton coming 1st, Stirling Moss and Peter Walker 2nd and Peter Whitehead and Ian Stewart finishing 4th. The Ecurie Francorchamps car driven by Roger Laurent / Charles de Tornaco finished 9th. This marked the final appearance of the Jaguar C-type works team in the famous French race. In the making was another version of the C-type that had been designed to make amends for the 1952 debacle.

1953 C/D Prototype XP/11

Chassis XKC054

at Jabbeke

Jaguar C-type chassis XKC054 was to be built as a ‘Le Mans prototype’ with a revised chassis; the chassis remained largely the same as the standard C-type but was made lighter and listed in the Car Record Book (or Build Ledger) as ‘light alloy box frame chassis‘.

This is the last C-type chassis to be listed in the record book and no date of completion is given, indeed there are no dates at all; the remarks column simply states ‘Experimental‘ and from that one may deduce that XKC054 was allocated to the Experimental Department and re-numbered XKC201 by the factory.

The light alloy body, designed by Malcolm Sayer, was a cross between the standard C-type and the streamlined 1952 Le Mans cars but with a new aerodynamic body shape that was more efficient than those models. Unfortunately, apart from the brief entry in the build records, no detailed specification of the model, variously known within the factory as XK 120 C Mark II, ‘the light alloy car’ or XP/11 exists.

We do know that it was completed by May 1953 and fitted with XK engine E1002-8 which had been fitted to XKC002, as driven by Stirling Moss and Jack Fairman at Le Mans in 1951, and by Moss at Dundrod and Silverstone that same year. That car (XKC002) was ‘reduced to produce’ by Jaguar late in 1952 with various components being used as required on other C-types in-build.

Introducing XP/11

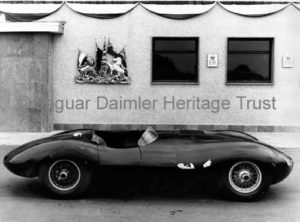

May 1953 – the first image of XP/11

to be issued for publication.

The new car, which we will refer to as XP/11 for convenience, was revealed to the Press in May 1953, as ‘A Jaguar Le Mans Prototype’ but with no technical information being imparted by the factory. Jaguar’s Press Officer Bill Rankin supplied no details and simply stated that it had a ‘new body’ and ‘…for this year’s race the “stock” C-type bodies will be used.’ No model name or number was given with the release.

XP/11 outside the main office

entrance at Browns Lane.

XP/11 was fitted with a 3.4-litre XK engine fed by three Weber 40 mm twin-choke carburettors in place of the SU units that had been featured on the C-type. It would appear likely that the XP/11 had the same wheelbase of 96 in (244 cm) and front track of 51 in (130 cm) as the C-type.

We have to assume that the length was probably the same as the long nose C-type of 1952 at 167 in (424 cm), but could have been an inch or two shorter as the nose and tail do not appear to be as pronounced as the 1952 car, which was ten inches longer than the standard C-type.

Sadly, this is speculative, as no details exist in the records or archives of this nature.

Build Methods

Rear three-quarter view of XP/11 showing the C-type-like spare wheel compartment and the four-spoked steering wheel.

Looking at the few photographs that survive of the XP/11 we can only speculate on its method of construction. The tubular chassis carried the engine, as per C- and D-type, though some who remember the XP/11 say it was more like the latter in arrangement, and that the frame continued through the bulkhead alongside the transmission. The tubular frame carried the engine with the outer members of the frame intersecting with the front bulkhead at its extremities. Instead of steel, magnesium alloy was used for the frame and, unusually for the time, Jaguar welded and not bolted the frame together. Argon arc welding had recently been developed and was already in use in the aircraft industry, as was magnesium alloy, but had yet to be applied to motorcar manufacture. This was a pioneering application by Heynes for a build method that has become standard, brave at the time, but it worked, making the XP/11 a strong and lightweight monocoque.

When first completed the XP/11 had a cockpit similar to the C-type with a low screen on the driver’s side, not unlike that of the ‘long-nose’ 1952 Le Mans contender. The space for the passenger/mechanic was as spartan as before and when not in use was protected with a canvas cover. Exit and entry may have been easier as the doors on both sides do not look as deep as the C-type. The unstressed bonnet hinged forwards like the C-type and much of the external furniture came from the C-type parts bin. Unlike the C-type, the exhaust pipe, which had a section of the nearside body cutaway to accommodate it, was located under the body on the nearside and then followed the same path as the normal C-type. There is no reason not to assume that the interior fittings, instruments, seats etc were taken from the C-type; Jaguar would not have sanctioned funds for any major changes for this one-off prototype. We do know from Norman Dewis that the steering wheel was a pre-war Bluemel four-wire-spoked item that was in store.

Underneath the XP/11 it was largely C-type, the front suspension and rear suspension was the modified version by Gerry Beddoes that would be used on the 1953 C-types. (Beddoes would later work on many different engineering aspects for Jaguar including the design of a military V8 tank power unit.) From the outset XP/11 was equipped with disc brakes and it is likely to have been fitted initially with a single dry-plate clutch as used at the time by the C-type. When the XP/11 was used for some high-speed runs at Jabbeke in October 1953, it was probably given a Borg & Beck triple-plate racing clutch.

The body, as has been noted, was quite new and shared few design features with the C-type; the rear section looks similar but the front section bears more than a passing resemblance to the D-type, even the small air intake is more like the latter. The headlamps were faired in behind a Perspex screen like the C and D-types and with the sloping nose has something of the E-type about it. Sayer had crafted a body that may be seen as a clear link between the C and D-type with design cues going on to the next generation of competition cars. Later on the XP/11 was given the suffix ‘C/D’ though not, it would appear, by the factory. Although having said that, William Heynes in a later chart of the power output of the XK 120 through to the D-type called the XP/11 ‘1953 Prototype of the D Type’.

Test Programme

The purpose of the car was to run a test programme to gather data for the competition Jaguars. Norman Dewis, who had replaced Ron Sutton as test driver in 1952, was given the task of testing the XP/11. Dewis first tested the car at Lindley on 13 May 1953 and reported a few faults including that steering qualities made the handling poor. He drove the car again on 17 May but this came to an abrupt halt when the nearside hub broke at speed. When the car was recovered it was found that the mounting bracket for the rear bearing of the offside upper suspension arm had also sustained some damage with a half-inch crack. There was talk about welding the crack but in the end the tried method of simply drilling a small hole at each end of the crack was done and testing carried on. Norman produced a report and suggested several changes or modifications that included the use of the latest brake discs and callipers from Dunlop when they became available. These were still in development and Norman was involved in those trials as well. Testing continued with the XP/11 before it was placed in store while the C-types were made ready for Le Mans.

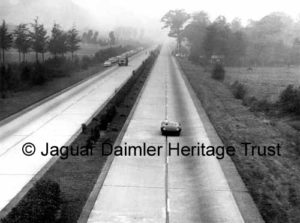

October 1953 XP/11 at Jabbeke

Lofty England (left), David MacDonald of Dunlop stands next to Norman Dewis in the centre and Jaguar mechanics Len Hayden and Joe Sutton. Disc brakes are visible through the spoked wheels.

The next time we hear of the XP/11 is when it was taken, almost as an afterthought, together with the modified XK120 by F R W Lofty England, wearing his Jaguar’s race manager’s hat, to Jabbeke in Belgium. The purpose of this visit was to see how fast the XK120 could go; it had a faired in bubble canopy and several modifications made to the standard body. Norman Dewis drove the XK120 to an astonishing 172.412 mph on 20 October 1953. He then turned to the XP/11, which had also been fitted with a bubble canopy, but had a small canvas fillet between the top of the driver’s door and the bottom of the canopy. Norman remembers that the car was “…disappointing that day, it kept misfiring. I could feel it and later on when we checked we discovered fuel starvation with a sticking diaphragm on the fuel pump.

Though it may not look it in this photograph XP/11 is exceeding 150 mph as it speeds down the Jabbeke highway on the way to reaching

178 mph.

We recorded 179.817 mph but if we had had a fully-functioning fuel system we would easily have got to 190 mph. I am certain of that. The car wanted to go faster!” Weather conditions were not good, there was a bad cross-wind that had given Norman some concern in the XK120 but he bravely carried on and four runs in the XP/11, which was must steadier in the cross-wind, were completed. Norman was pleased that Malcolm Sayer was there to see the XP/11: “His design was much more efficient than the XK120 and the bubble canopy also helped an already good design”.

Jaguar made a great deal of the XK 120’s performance that day but not much was made of the XP/11 which was loaded back on its trailer and taken back to Browns Lane via the cross-channel ferry. Norman himself thinks that the XP/11 was going to be built as the “…next Le Mans car and [Jaguar] would have raced the C in 1953 and the XP/11 the next year. The idea was to use Sayer’s new body style which was far more efficient.” Sayer continued to work on the front and rear ends of the XP/11 with a view to lowering the drag factor, as Norman recalls: “His calculations led him to the D-type and we went straight to that for 1954 and the light alloy car was dropped.” As an aside, the poster and the cover of the programme booklet for the 1954 Le Mans 24-Hours race depicts the XP/11 in the lead.

Continued Testing

That was not the end of the prototype as it was used by Jaguar to test all manner of axles, engines, gearboxes and power-assisted brakes for the D-type; so that when that model was ready to race in 1954 all the essential development work had been completed. Dunlop had been loaned C-type XKC011 for tyre development and in January 1954 XP/11 joined it at Silverstone for some tyre tests. Norman Dewis, along with Dunlop test drivers, drove both cars. Stirling Moss was also testing cars at Silverstone that day and was naturally interested in the XP/11; it would appear that England gave him the opportunity to drive the new Jaguar and Moss returned a lap time of 1 minute 58 seconds in the XP/11, faster than he had achieved in the C-type, which he also drove for comparison. Norman Dewis also recalls that another driver, who was given the opportunity to drive XP/11 that January day at Silverstone, spun off at Hangar Straight. There was no damage to the car but some to the ego of the driver, who later became quite well-known on the sports car racing circuit.

Bob Knight oversaw the trials of Jaguar development cars and the XP/11 was no exception. He collated all the data, which included disc brake tests at Gaydon, and initiated any modifications required to the car. All these data were pertinent to the emerging D-type design. By the end of January 1954 XP/11 had recorded over 3,000 miles on the track and on the open road. In those days all manufacturers used dual carriageways and local roads for testing, some at speeds that would certainly not be permissible today.

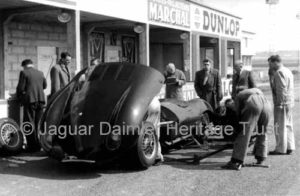

April 1954 XP/11 at Reims during trials of the Dunlop Stabilia tyres.

In April 1954 Norman Dewis took XP/11 to Reims for further tyre testing for Dunlop; XKC011 was also on strength. Jaguar had been concerned about the performance of Dunlop R1 tyres on the C-types and urged Dunlop to develop a stronger alternative. The British tyre manufacturer was quite willing to take up the challenge and the world’s first radial, steel-belted, low-profile racing tyre was ready for testing. Known as the Dunlop ‘Stabilia’, ahead of Le Mans in 1954, the XP/11 and C-type spent a week at Reims with Dewis and Peter Whitehead testing the tyres to near destruction.

April 1954 well-known photograph of Peter Whitehead driving XP/11 at Reims during the Dunlop tyre tests.

For this the wheel rims had been increased in width from 5.0 in to 5.5 in; the tyres were still 6.50 x 16, as were fitted to all C-types.

Dunlop tested their new tyre alongside the existing R1, changing the tyres as required but not telling the test drivers which type of tyre was being used. Norman remembers that Peter Whitehead returned consistent lap times regardless of the tyre-type but he found that he was lapping two seconds faster with the Stabilia. The tests also showed that the new tyre was far better and did not wear out anywhere near as quickly as the R1.

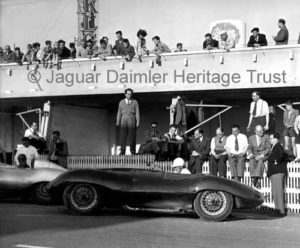

June 1954 the prototype D-type (in the background) was tested at Le Mans along with XP/11. Tony Rolt drove the D-type, Norman Dewis driving XP/11.

Among the spectators are William Heynes, William Lyons and Bob Knight

standing behind.

Also, tested at the time, on the C-type, were the new cast-alloy wheels from Dunlop, they also proved their worth and became standard on the D-type. Following the week in April, Norman drove the car to Le Mans and was able to run it around the road circuit which had been closed to other traffic.

To witness the XP/11 and the D-type’s Le Mans debut, Jaguar personnel included, William Lyons, Heynes, England and Knight among others.

What happened to the XP/11

What happened to the XP/11 after Le Mans and Reims? It remained on the strength of the Experimental Department and was used for developing other systems, including fuel injection. Lucas and Simmons (SU) provided two different systems for testing and these were installed in XP/11 with Lucas being selected. A test at the MIRA facility near Nuneaton in November 1954 was carried out to compare the Weber carburettors and the Lucas fuel-injection system. First the car was run on the Webers and then with the Lucas unit; the final results showed that the fuel-injection gave ‘…a saving in fuel consumption of 25 per cent in round figures…with a general overall improvement in the performance characteristics.’ Norman Dewis carried out the tests and recalls that the engine was much smoother with the Lucas system.

After these trials the trail of XP/11 goes cold, it had been overtaken by the D-type programme and was (probably) stored in the Experimental Department. Norman remembers it “being around the works” for a while but it is almost certain that by 1956 the car had been ‘reduced to produce’ with all usable parts going into store to be fitted to other C and D-types as required.

What does remain is a fascinating example of Malcolm Sayer’s thinking as he made the transition from the lovely C-type through to the purposeful D-type.

Author: François Prins

© Text and Images – Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust