Jim Randle

Director of Product Engineering – an appreciation by his son Steve

Jim Randle 1980

Director of Product Engineering (JDHT)

My Dad, Engineer Jim Randle, died at home on the 6th July 2019 after a prolonged battle with cancer.

Jim served his apprenticeship at Rover, where the P6 2000TC was his first major project. He then moved to Jaguar, where he was swiftly promoted to Head of Vehicle Development. As a boy I often accompanied him to his office in the corner of the development shop at Browns Lane on a Saturday morning.

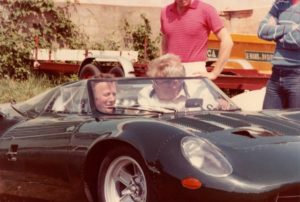

Jim, with George Mason in the

restored Jaguar XJ13 at Le Mans

© Steve Randle collection

I recall the fondness Dad was held in by the guys in the office (including Paul Walker, who was himself later to rise to the upper echelons at Jaguar), but notably also the workshop technicians led by the no-nonsense George Mason.

It was a period when the XJ13 was disinterred and restored using misappropriated funds and labour – a Randle skunk works project in the same mould as the XJ-S cabriolet and XJ220 would be many years later.

The XJ-S was Jim’s first baby at Jaguar, created in the era when Bob Knight was engineering director. He would regularly have Dad chewing the carpet, but he was always clear that Bob was the finest engineer he ever met – “I learned more from that man than any other I’ve ever known”.

1987 Jim Randle receiving the

Top Car Award for XJ40 (JDHT)

Jim subsequently became Engineering Director himself, where he masterminded the XJ40 – Jaguar’s first all new car since the 1968 XJ – which was launched in 1986. To drive one today is to understand the watershed between modern and vintage cars. It was the cornerstone of Jaguar’s revival under John Egan, continuing in its updated X300 form until 1997.

In many ways, the ’40 was Dad’s finest work – not simply for the fine motor car that it is, but also in that it represented the engineering team created to deliver it. This period also saw Jim drawing Sir William Lyons back to Jaguar after a period of disaffection during the darkest days of British Leyland. Sir William became a regular sight in the styling department once again, wielding his walking stick with authority. Jim loved him.

Jim and his wife, Jean following Jaguar’s 1988 Le Mans victory.

“I’ve never been happier”

© Steve Randle collection

The 1980’s saw Jaguar return to the track, firstly with the Group A TWR XJ-S, the Group 44 XJR-5, and ultimately the Le Mans win in 1988 with the XJR9, all under Jim’s support.

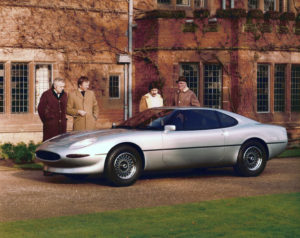

John Egan, Jim Randle, Keith Helfet &

Sir William with XJ41 (JDHT)

The beautiful XJ41 bi-turbo sports car was to be based on the XJ40 platform, but was sadly cancelled as funds ran short during the era of Ford ownership.

Some solace for this was found in the birth of XJ220, although XJ41’s progeny did ultimately find its way into production as the Aston Martin DB7.

The XJ220 began life as the offspring of Jim’s Saturday club, where Jaguar engineers, and devoted suppliers such as Park Sheet Metal, would give their own time to create something special. They truly achieved that, with the 48 valve 6 litre all wheel drive supercar originally built to meet Group B regulations appearing at the 1988 Birmingham Motor Show.

Dad and I built the first structural concept for 220 on our sitting room floor, in cardboard and foam core one Christmas.

The late 1980’s and early 90’s saw Jim becoming increasingly disenchanted with the company under the Ford ownership, particularly as he was forced to watch some of his best engineers leave, and soon followed them himself.

He continued to apply his visionary approach afterwards. He was a vocal advocate of hybrid technology long before he left Jaguar, and particularly of compressed natural gas and micro turbines as constituent elements. He was clearly right about hybrids, and I fully believe he will be shown to be right about turbines and CNG, as the technology to synthesise methane from airborne CO2 using renewable resources is becoming a technical and commercial reality. Volvo’s 1992 ECC showcased Jim’s work in this field. He was also right about electrical energy recovery from turbochargers, having pioneered the concept with Perkins long before they appeared in Formula 1.

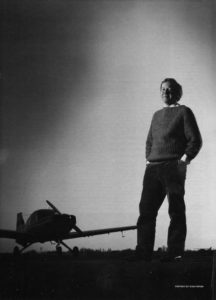

Jim Randle

© Steve Randle collection

Jim later applied himself once again to sports car design with the all-aluminium Lea Francis 30/230. Only one was built (which we still have), but its chassis was adopted for the Morgan Aero8.

Throughout his career, he was always quick to deliver praise where it was due – to his own people and to other designers. He was happy to forgive my shocking Citroën habit, and often said that the 2CV was about as good a car as anyone ever designed. Jim’s love of sailing and aircraft ran parallel threads to his motoring career. We built sailboats and a sailing dinghy together – the latter in my bedroom – and I learned much of his patient first principles approach as we did so. He continued to fly light aircraft until he was 80.

His illness finally took him, aged 81. He leaves me, my sister Sally, five grandchildren of whom he was very proud, and a legacy of which we all can be.

Author: Steve Randle

© Text and Images – Steve Randle – except (where stated)

Sources and Further Reading:

-

Lord Montagu of Beaulieu and foreword by HRH Prince Michael of Kent, Jaguar (Quiller Press, 1997)

-

Mennem, Patrick, Jaguar: An Illustrated History (The Crowood Press Ltd, 1991)

-

Whyte, Andrew, Jaguar: The Definitive History of a Great British Car (Patrick Stephens Limited, 1990)

-

Hull, Nick, Jaguar Design: A Story of Style (Porter Press International, 2015)

-

Daniels, Jeff, Jaguar: The Engineering Story (J H Haynes & Co Ltd, 2004)

-

Thorley, Nigel, Jaguar in Coventry: Building the Legend (Breedon Books Publishing Co Ltd, 2013)

-

Skilleter, Paul, Norman Dewis of Jaguar: Developing the Legend (PJ Publishing Ltd, 2017)

-

Porter, Philip and Skilleter, Paul, Sir William Lyons: The Official Biography (Haynes Publishing, 2001)

-

Porter, Philip, The Most Famous Car in the World: The Story of the First E-type Jaguar (Cassell, 2000)