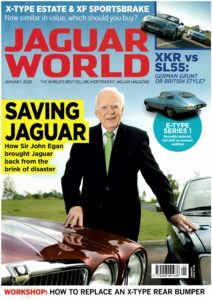

Sir John Egan

Saving Jaguar

Jaguar World January 2020 © Jaguar World

Reproduced with permission of Jaguar World magazine (January 2020) and Ray Hutton.

Ray is an internationally-renowned journalist, former editor of Autocar and author of Jewels in the Crown: How Tata of India transformed Britain’s Jaguar and Land Rover (Elliott & Thompson, 2013)

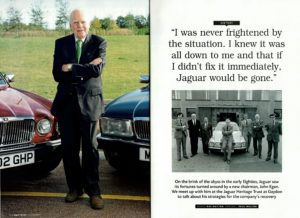

On the brink of the abyss in the early Eighties, Jaguar saw its fortunes turned around by a new chairman, John Egan. We (Jaguar World) meet up with him at the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust at Gaydon to talk about his strategies for the company’s recovery.

For Jaguar, it was the ultimate indignity. The British Leyland Motor Corporation renamed its Browns Lane factory: Large Car Assembly Plant No2. The marque that Sir William Lyons had created and nurtured was in danger of becoming simply a model line in a range of Leyland cars. When British Leyland came into being in 1968 it brought together the brands of the former British Motor Corporation with Jaguar, Daimler and Leyland’s Triumph and Rover. In a message to employees, BLMC chairman Lord Stokes said, “Jaguar will be able to pursue its own course, within the overall policy of the group.”

When Sir William Lyons retired in 1972, his long-standing lieutenant FRW ‘Lofty’ England became managing director. A year later, British Leyland replaced him with 34-year-old Geoffrey Robinson. Backed by Lord Stokes’ assurances, Robinson announced a £60 million investment in Jaguar and a plan to double production from 30,000 to 60,000 cars a year.

Jaguar World – January 2020

Pages 28-29

The next year, 1974, Robinson’s big idea itself faced the abyss as Sir Don Ryder, of the Government’s National Enterprise Board, prepared a ‘rescue plan’ for the unwieldy and heavily loss-making Leyland conglomerate. The Ryder Report called for a rationalisation of marques and models, grouping them all together as one profit (or loss…) centre, pooling all resources and facilities, and relegating the identities of individual brands to little more than badges.

As a result, British Leyland was effectively nationalised. Lord Stokes stood down. Jaguar would no longer have its own CEO, and Robinson and his ambitious plans were ousted.

Unless you were there, it is hard to imagine the turmoil in Seventies Britain. The Swinging Sixties, with its promise of a bright new future emerging from post-war austerity, was over. Social divisions and industrial unrest set the tone; a miners’ strike brought black-outs and a three-day working week to conserve fuel supplies. Inflation was rampant – nine percent in 1973, 24 percent by 1975. And the winter of 1973 brought the first Oil Crisis, when, following the Arab/Israeli war, oil producers in the Middle East increased the barrel price by 70 percent.

The British motor industry was in decline, at least in part because of management complacency and lack of investment. Many of its products were of poor quality and unreliable and consumers began to look at imports, encouraged to some degree by the UK joining the EEC (Common Market) in 1973. British Leyland led the UK new-car market in 1971 with a 41 percent share, but, by the end of the decade, it had just 23 percent.

Although Jaguar had still been profitable in 1974, after nationalisation its profits were subsumed by the losses at Austin-Morris. The Ryder plan turned out to be hopelessly unrealistic about British Leyland’s prospects and did nothing to address chronic over-manning and the union shop stewards’ ability to call damaging strikes at a moment’s notice.

Somehow – and largely to the credit of its engineering chief, Bob Knight – Jaguar engineering managed to remain separate from the Group amalgamation of design and development, centred at Rover, in Solihull.

Jaguar World – January 2020

Pages 30-31

Jaguar introduced the XJ-S at this time as a controversial replacement for the much-loved, but 15-year-old E-type. Marque loyalists were dismayed to find it hidden among the Austins, Morrises, Triumphs and Rovers on a corporate British Leyland stand at the 1976 Earls Court Motor Show. Jaguar also had in preparation the XJ40 – a successor for the XJ saloon – and the new AJ6 straight-six engine, but was not able to get the green light from the BL board to proceed to production. Instead, it had to carry on with the existing XJ, freshened up with some neat re-styling by Pininfarina.

In 1977, Prime Minister James Callaghan appointed South African Michael Edwardes as chairman and CEO of British Leyland on a five-year contract. As well as taking a hard line with the unions – BL lost 32 million man-hours to strikes in 1977 – the no-nonsense Edwardes recognised that the Group’s marques needed to be cherished, not diminished, and quickly re-instated a Jaguar board (with Bob Knight as managing director). A specialist cars sub-group, Jaguar Rover Triumph (JRT) was established and Edwardes asked a young man who had reorganised BL’s parts business to run it. That young man was John Egan, who had since left BL for Massey Ferguson in Canada. He turned the JRT job down, as he saw no future for Triumph and thought he would not be able to secure the funds that Jaguar and Rover needed in competition with other, larger, parts of the group.

John Egan

JRT lasted only a couple of years before Rover and Triumph joined with the mass-market division. Edwardes, now Sir Michael, identified Jaguar and Land Rover as the luxury brands of the re-named BL Cars. He approached Egan once again. This time, the proposition was that he would be chief executive of Jaguar Cars, as a separate entity within the Group – and with a free hand to turn the business around. Egan, who had just turned 40, accepted the challenge.

He took up his new appointment at Jaguar’s Browns Lane headquarters in April 1980. It was the start of a new era for Jaguar, which brought it back from the brink of closure and onto profitable independence, very much in the style of Sir William Lyons’ original company. Sir William could be proud to be acknowledged as Jaguar’s honorary Life President.

Sir John Egan was, like Sir William, born in Lancashire, and his family moved to Coventry when he was a child. He trained as a petroleum engineer at the Imperial College London and worked for Shell in the Middle East before joining AC Delco, a division of General Motors. He was head-hunted to join British Leyland’s central staff in 1971 and brought together the company’s parts business under the Unipart brand, ending up as the group’s parts and service director.

Egan knew he had signed up for a tough job. Although separate accounts were not published, by then Jaguar was heading for a loss of some £50 million. Productivity was deplorable – 9,200 employees had produced fewer than 15,000 cars in 1979 – and quality problems had led to crippling warranty claims. Edwardes told him that if Jaguar could not be turned around and its losses reversed it would be closed. The dire situation could not have been clearer when he arrived at Browns Lane that April morning and saw that he would have to cross a picket line to gain access. Jaguar was on strike and the production lines were stationary.

Jaguar World – January 2020

Pages 32-33

Sir John tells us, “I had no idea of the situation [Jaguar on strike] as I had been on holiday in Italy with no newspapers or contact. I assumed that everything was tickety boo. I knew the awful mess that BL was in, but didn’t think it would be as rough as it was. I had created the Unipart business and knew I would have to do everything myself. It was going to be a highly personal endeavour. But I made a lot of progress that day, as I became chairman, as well as managing director.”

The dispute was over BL’s introduction of job grading across the corporation. Jaguar workers saw themselves as a cut above their counterparts at Austin-Morris – as craftsmen rather than assembly line operatives. Edwardes, encouraged by the new Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, was engaged in a determined fight to limit union control and would not yield.

Saving Jaguar

by Sir John Egan

Egan remembers Percy Plant, his chairman, saying it was not Egan’s problem and that he should go home and wait for things to settle. Retreat wasn’t Egan’s way. He wrote in his book, Saving Jaguar, “I told him that I didn’t want to be the only chief executive of a car company never to make a single car.” So the two of them decided on a plan of action: Plant would stand aside as chairman so that Egan, as the newcomer with a promise of independence, might negotiate where others had failed.

It was a critical decision, and it worked. Egan, as chairman and chief executive, called a weekend meeting with the shop stewards. He underlined his complete commitment to Jaguar and that he would work ceaselessly to resolve its problems and return the business to profitability, thereby justifying investment in new models and facilities. In other words, if we work together, Jaguar has a future.

The unions held a vote on the Monday and, by a narrow margin, agreed to return to work. Egan’s recovery plan could begin. Improving quality was a priority. In September that year, at Egan’s invitation, I had gone with three of my Autocar colleagues to a meeting at Browns Lane. Unusually for a press interview with a car company boss, two union shop stewards were there. Egan had told us, “It’s important that they hear what I am saying to the outside world.”

That day, he promised to get tough with Jaguar’s suppliers. “We are on a single-minded crusade for excellence. It’s no secret that many of the quality and reliability issues associated with our cars can be traced back to ’bought out’ components. We are not prepared to tolerate unsaleable quality from our suppliers. If a supplier is letting us down he will be given a chance to put it right – but only one chance. If he cannot deliver the quality we require we will go elsewhere, and there will be no right of appeal.”

But the biggest quality problem of all came from within BL Cars. Castle Bromwich, the huge factory that made Spitfires in World War Two, produced and painted all Jaguar’s bodies, but it was actually part of Austin-Morris and its new thermo-acrylic paint process simply didn’t work properly. Mike Beasley, Jaguar production director, reported that it could only paint in yellow, red and white – colours that didn’t suit the XJ Series 3 – and even then, the finish was unacceptable. Every one of the bodies coming out of Castle Bromwich had to be re-worked and re-painted at Browns Lane. Austin-Morris wanted to close down Castle Bromwich, but as Jaguar had no alternative body supplier, Egan engineered the transfer of the enormous factory to Jaguar and set about rectifying the faults in its processes and equipment.

At the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders’ dinner preceding the motor show at the National Exhibition Centre, Margaret Thatcher bemoaned the fact that 1980 would turn out to be the UK’s lowest car production in 20 years. She observed, “British people are buying foreign cars, some from high-wage economies. If they can design cars that people want, why can’t we?” Egan tells us that he countered with a typically confident, if optimistic, statement, “I’ve got to dominate the top car market. Jaguar has to beat Mercedes and BMW.”

John Egan (in front of XJ6 Series 3)

and Sir William Lyons

By September that year, Egan had secured – from BL and, therefore, the Government – a £90 million investment, and approval for the XJ40 project (it had started back in 1972 but was put on hold when the current XJ was given a second facelift in 1979 to become the Series 3). At that year’s motor show, he was able to announce, “Jaguar’s autonomy is almost complete. The company is in a new position as a separate entity in the BL Cars Group.”

Irritatingly, sales remained centralised and Jaguar had to pay BL to sell its cars – that was the next thing to be sorted out. Commercial independence was achieved bit by bit, first in the USA where Graham Whitehead moved from BL International to Jaguar full-time, then in the UK home market where Egan appointed Roger Putnam sales director, and later in other overseas markets, under export director John Morgan.

Production increased quickly from 14,865 in 1980, Egan’s first year, to 28,000 by 1983, close to the 30,000 break-even figure that Edwardes had set as the target for Jaguar to be guaranteed to stay in business. However, financially it had already turned the corner thanks, in the main, to US sales and a favourable dollar exchange rate.

Standing among the cars at the Gaydon Jaguar Daimler Heritage Centre, Sir John Egan points to the last XJ6 Series 3 to be produced and tells me that he had quickly realised Jaguar was better off continuing to sell it than rushing the development of its replacement, the eventual XJ40.

He says, “I knew if I could make them right, the Series 3 would be a lovely car. I think I managed to motivate everyone to make quality our number one obsession. Nobody, not even the union shop stewards, could tell me I was wrong. In the first six months, we made incredible improvements. It took about a year to make the cars work properly, so within 18 months they were saleable and within two years they were profitable.

“My first action had been to improve the integrity of the body – once you have a body with good, consistent dimensions, things fit better. The people at BL Body & Assembly Division at Castle Bromwich were not all that bothered about structural integrity. I had to take control. So, we took over Castle Bromwich – and its losses – within the first few months. Mike Beasley fixed both body assembly and the troublesome paint plant. Without that, we wouldn’t have made it.”

As a result of his dogged determination, the XJ Series 3 – with body assembly and paint problems sorted out – was a success.

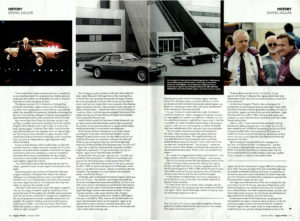

1981 Nigel Mansell taking delivery of XJ-S from John Egan

The XJ-S was fitted with the HE (high efficiency) version of the 5.3-litre V12 engine that consumed less fuel than the original, but also met tightened exhaust emissions regulations; sales of the XJ-S had dropped to 1,100 in 1980, but the HE gave it a new lease of life, as did the first open-topped version, the Cabriolet, the first model offered with the new 3.6-litre AJ6 engine.

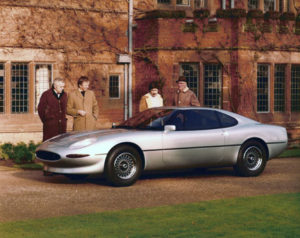

John Egan, Jim Randle, Keith Helfet & Sir William with XJ41

In the engineering department, work was progressing on the XJ40 and starting on the XJ41, Jim Randle’s idea for an Eighties E-type successor.

Sir John admits that he probably made a mistake with the XJ40 at this time, “By not going back and starting the XJ40 all over again. I think I could have made a better car and, by then, we had enough engineers to do it.”

From the start of his tenure, Egan had envisaged an ultimate goal of a complete break from BL, but it was far from certain that Jaguar would be privatised.

“Independence was the motto,” he tells me. “It was agreed with Michael Edwardes that Jaguar would have to be independent of BL Cars, but we would only have as much of it as we deserved.”

At that time, Margaret Thatcher was encouraging the privatisation of nationalised industries and made it clear to BL that future funding would be dependent on selling off some of its elements. Jaguar was identified as an early candidate – Egan had returned it to profit in 1982, had improved quality and productivity with a slimmed-down workforce, and had a viable future product plan.

Adds Sir John, “I was convinced that we should build up resources to add an executive car to the range. So, I would have needed to sell 100,000 of the existing cars [XJ and XJ-S] to raise the £500 million that would cost. Of course, we could have raised money for the third car elsewhere, but that would have put us into debt and I was frightened of the risk associated with debt.”

Egan investigated the possibilities of a management buy-out, or investment from – or takeover by – another car company. Although there were exploratory talks with BMW, Ford and General Motors, it became clear that the Government preferred a public flotation, retaining a ‘golden share’ to prevent a raid by an unsuitable bidder.

Jaguar went to the stockmarket in August 1984 with a share price set at 165 pence. The issue was eight times over-subscribed. Egan was not entirely comfortable with that as he knew he would have to defend the share price once it had started, but since it only crept up in the first years as an independent company, he accepted that the underwriters had got the price right.

John Egan was chief executive of the new company. BL had nominated Hamish Orr-Ewing, chairman of Rank Xerox (who drove an E-type) as non-executive chairman, but he seemed set on diversification into other industries (boats, aircraft) with which Egan could not agree. So, Orr-Ewing was dismissed and Egan became both chairman and chief executive.

Sixteen years under British Leyland was not going to be dismantled in an instant; contracts had to be drawn up for the continuing supply of parts and services from BL companies. However, Jaguar made a major strike for independence by establishing its own, greatly enlarged technical centre at the site of the former Chrysler R&D buildings at Whitley, near Coventry (today, the location of Jaguar Land Rover headquarters).

Jaguar continued onwards and upwards. In 1985, production reached nearly 38,000 with a pre-tax profit of £121 million – and the XJ40 was still to be launched. Egan initiated a racing programme with the objective of repeating Jaguar’s Le Mans wins in the Fifties, stimulating its engineers and generating worldwide prestige.

1987 John Egan with the Jaguar Board and the new XJ40

His achievements of returning Jaguar to profit and successfully taking it private was recognised by a knighthood in 1986, the year the XJ40 finally appeared (14 years after it had first been mooted). Sales volume in 1986 had been up again, with more than half the cars destined for the USA.

In 1988, Jaguar production reached 50,000 for the first time. The XJR-9 won the Le Mans 24 Hour race and encouraged sales of the re-engineered full convertible version of the XJ-S.

Jaguar World

January 2020

Page 34

The XJ40’s initial reliability problems (attributed to introducing an all-new model and increasing production at the same time) had been resolved and it was selling well, and the race-inspired XJ220 supercar wowed the crowds at the NEC Motor Show. Jaguar was still riding high, but the company’s necessary dependency on the American market (half of all customers who could afford a Jaguar were in the US) made it vulnerable when recession loomed, stock markets crashed, and the pound strengthened against the dollar. Sir John Egan and the Jaguar board began to worry about money – and the future.

Lindsey Halstead, head of Ford Europe and John Egan

They concluded that, for Jaguar to survive and thrive, it would need to collaborate with one of the bigger players in the motor industry. Their idea was not to sell the company outright, but to accept a minority shareholding in return for technology, components and facilities.

Jaguar began to look for partners to share these costs and inevitably attracted takeover bids, although it was theoretically protected by the Government’s golden share, which restricted any one shareholder to 20 percent.

I ask him about that time. “Ideally, we wanted to tie-up with Toyota so that they could keep a benevolent eye on us and we could help with their new luxury car business (Lexus). They told me, ‘No,’” he replies. “I was hoping that, with the golden share in place, a number of investors would each buy 20 percent. It could have happened. But then, Nicholas Ridley cancelled the golden share.”

But there was no retort to the killer takeover bid that came from the Ford Motor Company in October 1989.

It marked the end of the Egan era of glorious independence and the start of a new phase in Jaguar history – as a subsidiary of the world’s second largest car manufacturer.

__________________________________________________________________________

Looking Back

Sir John Egan reflects on decisions made at the end of his time at Jaguar

Sir John Egan at Gaydon December 2019 with the last of the line XJ6 Series 3 and last of the line XJ40

© Jaguar World

Sir John is on record as saying that Ford was the worst option available, but that he had no choice other than to recommend its bid – five times the company’s assets – to shareholders. He looks back at this period and the end of his time at the company.

“Did I make any mistakes? I think I did,” he reveals.

“I think I should have tried harder to find Jaguar a better home. Toyota would have been brilliant, but I was told later that if I had gone to Nissan they would have taken us on – they were struggling with Infiniti, their premium brand. Or, if we had gone to someone like Peugeot, we could have done a better job and kept our independence.

“If I had done a deal with Ford and stayed, I could have told them the one thing they needed to know: they could make a success of Jaguar as long as they tried to make the best car in the world. But Ford only knows how to run things its own way.

“As it turned out, Ford did an honest job with Jaguar. They didn’t run away and they poured money in, but did they understand what they were doing? No. They should have tried to make the best cars in the world.”

Words: Ray Hutton

Portraits: Paul Walton

Images: © Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust except where stated as Jaguar World

Sources and Further Reading:

-

Lord Montagu of Beaulieu and foreword by HRH Prince Michael of Kent, Jaguar (Quiller Press, 1997)

-

Mennem, Patrick, Jaguar: An Illustrated History (The Crowood Press Ltd, 1991)

-

Whyte, Andrew, Jaguar: The Definitive History of a Great British Car (Patrick Stephens Limited, 1990)

-

Hull, Nick, Jaguar Design: A Story of Style (Porter Press International, 2015)

-

Daniels, Jeff, Jaguar: The Engineering Story (J H Haynes & Co Ltd, 2004)

-

Porter, Philip, Jaguar: E-Type The Definitive History (Porter Press International, 2015)

-

Thorley, Nigel, Jaguar in Coventry: Building the Legend (Breedon Books Publishing Co Ltd, 2013)

-

Skilleter, Paul, Jaguar: The Sporting Heritage (Virgin Publishing, 2001)

-

Skilleter, Paul, Norman Dewis of Jaguar: Developing the Legend (PJ Publishing Ltd, 2017)

-

Porter, Philip and Skilleter, Paul, Sir William Lyons: The Official Biography (Haynes Publishing, 2001)

-

Porter, Philip, The Most Famous Car in the World: The Story of the First E-type Jaguar (Cassell, 2000)

-

Wilson, Peter D., XJ13: The Definitive Story of the Jaguar Le Mans Car and the V12 Engine That Powered It (PJ Publishing, 2011)