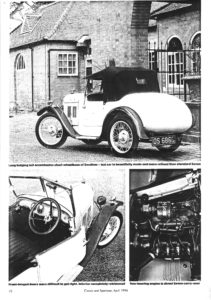

The first ‘Jaguar’ – Austin Seven Swallow DS 6866

Reproduced with permission of Classic & Sports Car magazine (April 1994)

© Classic & Sports Car Magazine 1994

Classic & Sportscar

April 1994

This is where it all started, with the Swallow-bodied Austin Seven.

Philip Porter tells how he restored the earliest survivor

How could we resist the challenge? Feline Motor Works, my restoration workshop, specialises in Jaguar XKs and E-types. But when Jaguar asked us to restore the oldest Swallow in existence, we were more than happy to oblige.

William Lyons and William Walmsley formed the Swallow Sidecar Company in 1922 and prospered. In 1927 they applied the coachbuilding skills of their company to that revolutionary concept, the small low-cost car, otherwise known as the Austin Seven. This creation of Herbert Austin’s was achieving his aim of bringing ‘Motoring to the millions’, but it lacked a certain style. Swallow built its own design of body which it fitted to the Seven chassis to create a small car of distinction and style.

Classic & SportsCar

April 1994

The first ‘Jaguar’

Austin Seven Swallow

DS 6866 – Page 71

In 1928, Swallow moved from its Blackpool birthplace to the more traditional motor manufacturing centre of Coventry and went on to better things – the SS cars, followed by the XKs, Es and a whole run of great saloons. Just three examples of those Blackpool-built cars are known to have survived and some years ago the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust acquired the earliest of them. Judging by photographs it had lapsed into a dilapidated state when acquired by an enthusiast in Redditch. He had commenced a full restoration and then sadly died. The Trust became the owner of this most historic car after it had stood for a number of years.

The car looked to be well on the way to completion with its aluminium bodywork bare and a selection of parts in boxes. But it proved, as the incomplete projects so often do, and as we suspected, to need a great deal more work than appearances suggested. As my colleague Peter Stant, who carried out most of the work on the car, put it; “When we came to sort out what was there and what wasn’t, there were more things that weren’t there, than were! There were lots of bits missing so we had no patterns. The body, although looking virtually complete, hadn’t been assembled correctly.”

Being such an early car, this Swallow differed from virtually all the other examples in existence. So a great detective job started. It was a matter of deciding what was missing, then working out the dimensions, form and appearance of each part and what they should be made of! We visited other owners, and looked at examples in museums as we built up our knowledge of the cars, but found that many of them were unoriginal. I have amassed quite an archive of photographs which often helps with rebuild, and to check certain features we examined with magnifying glasses period shots of cars and the little production lines.

By far the greatest help came from the Austin Swallow Register, of which I have been a member for many years as I own a saloon. It is a particularly friendly club and several stalwart members, such as Derek Mudge and Gil Mond, played a vital role in the car’s recreation. We were lent patterns, photographs and drawings with refreshingly unselfish enthusiasm.

Indeed, help came from all sources. The Daily Telegraph ran a story on the car and a reader donated the rare Swallow mascot which he had on his car in the ‘30s and which had been sitting on his mantelpiece ever since!

Having assessed the car in our workshops, it became obvious that we had to go right back to basics: the ash frame had been neither glued not screwed together properly. We removed the body skins and took apart the frame. Certain new parts needed to be made and others modified, and then the whole lot was glued and clamped. It was then screwed together using bronze alloy screws and the whole frame treated against woodworm.

Classic & SportsCar

April 1994

The first ‘Jaguar’

Austin Seven Swallow

DS 6866 – Page 72

Being hand-made originally, a number of the Swallow cars vary in various dimensions and unfortunately no factory records exit from those days. Peter recalls the difficulties: “We examined the pieces we had, to look for any screw holes or any evidence of brackets which had been fitted. By looking at the photographs we could work out the shape of something, and then judge its size by the spacing of the holes in the original parts we had.”

In this way the jigsaw was gradually pieced together. Meanwhile we found the chassis had rot, so we sent it away for expert repair. We had discovered wear in a lot of components, so we used the repaired chassis as a jig on which to start building the body. It was quite tricky at times to determine which were original parts, and thus safe to rely on as undisputably correct, and which were merely remade old parts which could not necessarily be trusted.

The entire interior was missing, which meant we had no floors, no bracketry, seats or dash. The gearbox tunnel was old but not original, which nearly led us astray. Fortunately, Swallow enthusiast Doug Fuller’s amazing memory for such details clarified this area for us. The body tail section was clearly original and this was some help but the method of fixing was not immediately obvious. Additionally the spare wheel carrier, which should be mounted inside the tail, was non-existent.

Here we nearly blundered. On examining yet more photographs, we found that one of the two other 1928 cars had hefty brackets in this area to support the spare wheel frame and rear body. We were all set to make up such brackets for ‘our’ car when further research revealed that the other car had been used for trialling. Its intrepid owner used to carry a coupled of sandbags in the tail to aid traction and had made the modifications.

The tail was original but dented and fatigued. It had to be annealed to remove the dents, and welded round the lower edges. One door was built, the other half-built. They fitted the door apertures reasonably well but needed stripping and glueing. Peter had to wheel the skins as they were flat and needed a little shape putting into them. The beading around the doors changed, differing styles being used in ’28 and ’29. And this detail took some sorting.

The original bonnet had been lost and the car, following an accident, had been fitted with an Austin Seven radiator shell. There were no original wings with the car, but there was a remade set. The fronts were acceptable, though they needed some re-working. The rears, however, were too narrow and had to be discarded. As we had a strict deadline to have the car finished in time for the London Motor Show (although the car was not exhibited until the Scottish Show) we substituted the wings I had made for my saloon a few years previously.

New running boards were straightforward to make from ash. We were unable to obtain the correct ribbed aluminium to make new covers but luckily the originals were repairable. They were acid-dipped to remove the oxidisation and cleaned up satisfactorily.

Classic & SportsCar

April 1994

The first ‘Jaguar’

Austin Seven Swallow

DS 6866 – Page 73

There was no hood frame with the car. The owner of the ‘trials’ car kindly lent us the remains of an original item, which helped considerably. Peter made up a new frame of metal and hand-formed, steam-bent ash. He spliced together two 90 degree pre-bent ash ‘hockey stick’ frame sections from Vintage Supplies. These he then shaped to the half-round profile with the traditional spokeshave, repeating the exercise for each hoop.

Meanwhile, due to time pressures and his greater Seven experience, we had entrusted some of the mechanical work to Mel Cal of Malvern. He rebuilt the back axle, supplied some propshaft parts and checked over the engine and ‘box, which had been rebuilt by the previous owner. Mel’s son made a new petrol tank and they recored the radiator.

All the brightwork was missing, with the exception of the screen pillar and screen frames. The outer screen pillars were profiled from rough castings which Derek Mudge was able to supply, and later chromed. The door handles came from Vintage Supplies and the locks were rebuilt.

The important and distinctive radiator cowl had been made some years previously and a superb job had been made of this, though a few dents had appeared during the car’s period of resting. Following careful panel beating and rubbing down, the cowl was polished and returned to its former glory. The correct brass mesh was supplied by the midland branch of the Seven Workshop, where Mick Kirkland was extremely helpful.

Meanwhile Ray Banks, a fine trimmer of the old school had been making progress. Ray is a mobile trimmer; he arrives at your premises in his van which carries his sewing machine, his workbench and various materials. Ray obtained some tatty, original seat skins and measured these, then went to great pains to use the correct materials in the correct way, with the right stitching. He made the seat springs and frames from scratch rather than relying on modern foams.

Peter Stant then concentrated on the mechanicals which needed completing. He made up the fuel feeds, the throttle linkages and the advance-retard mechanism from drawings supplied by Mick Kirkland. The choke linkage was an amusing aspect, as Peter recalls: “The choke is a very crude affair. There is just a penny washer on a spring which closes off the mouth of the carburettor and this is connected via a wire to a small ring under the dash which you pull when you want to start the car. When you let go, it springs back. The story goes that early Austin Sevens, which had the same system, were supplied with a clothes peg to keep the choke open!” I felt it was rather necessary to point out to Jaguar that this crude, flimsy set-up was as original rather than a Feline bodge.

A new starter motor and magneto had to be located. These were supplied and rebuilt for us by Mike Bolton of the Bolton Magneto Company of Wolverhampton. They arrived a little late in the day; as did the headlamps which we had been trying to trace from the beginning. These lamps are of the Chummy type and gave us sleepless nights. We finally obtained a pair four days before our deadline from an Austin Seven spares dealer who had been promising these and other parts continuously for several months.

The rear lights, and a number of minor parts came from Paul Beck Vintage Supplies. The single original type rear lamp had to be sympathetically modified to allow the car to pass its MOT, and again for legal reasons two extra rear lamps were fitted on brackets, but they can be easily removed if required.

While Peter was working on the mounting of the front cowl radiator and front wing stays, which again were quite a challenge as all the parts were missing, Ray Banks was making good progress with the trim. He covered the hood frame with brown paper patterns, which he then duplicated in double duck. Similarly he covered the side screen frames made by Peter.

Although the bonnet looked as though it had been well-made, we had to take it apart and re-form the folds for the hinges to allow the bonnet to lie correctly. After the necessary body profiling and preparation work, the body was painted by Steve Grimsley of Phoenix Car Restoration, at Eardsley in Herefordshire. He painted the main body first in the nearest shade of cellulose available. This was returned to the Feline workshops for Peter and Ray to continue as the deadline was approaching all too rapidly.

While Peter was completing the last tasks including the wiring, and fitting the exterior trim and suchlike, Steve was painting the wings, the wheels and the headlamp cowls. The wings were painted Damson red, which is rather appropriate as our workshop is surrounded by my damson orchard!

Classic & SportsCar

April 1994

The first ‘Jaguar’

Austin Seven Swallow

DS 6866 – Page 75

The engine genuinely started on the first push of the button and the MoT was obtained the afternoon before our deadline, after Peter had worked a few long days. It is a curious car to drive with minimal clutch movement, modest brakes and gentle performance, but it exudes great character.

The car’s arrival at the Jaguar factory coincided with the Board breaking their meeting for lunch. We were delighted when all the directors descended on the little car and showered it with praise which reflected great credit on Peter and our suppliers and sub-contractors. No-one was more enthusiastic than Jaguar chairman, Nick Scheele. Indeed, his enthusiasm must encouragingly endorse his respect for Jaguar’s heritage and William Lyons’ first car.

USEFUL CONTACTS [As of 1994]

| Feline Motor Works | 0584 795 88 |

| Ray Banks | 0789 762 768 |

| Phoenix Car Restoration | 0544 327 233 |

| Mel Cale | 0684 400 18 |

| Bolton Magneto Company | 0902 451 815 |

| Paul Beck Vintage Supplies | 0692 406 343 |

| Seven Workshop, Midland Branch | 0785 760 561 |

| JVR Refinishing Suppliers (paint) | 0432 263 606 |

Words and photography: Philip Porter

© Classic and Sports Car April 1994