Jaguar C-Type

The Race for Le Mans

Jaguar C-type

With a car conceived in a very short space of time Jaguar scored a major success in the famous endurance race.

The Jaguar XK120 had become an immediate success when it was launched in 1948. Originally it had only been a design exercise – to showcase the XK engine – that would be produced in limited numbers but pressure from dealers, especially from North America, saw the XK120 enter full-scale production at Foleshill. The early cars had aluminium bodies (steel being rationed and unavailable) and proved popular on the racing and rally circuits. Three cars had entered the British Racing Drivers’ Club Production Car race at Silverstone and took the first two places. Encouraged, Jaguar sold or lent six XK120s to six selected drivers for the 1950 Mille Miglia; Leslie Johnson finished fifth.

The most gruelling race of the day was the Le Mans 24 Hour Race and for the 1950 event Jaguar entered three cars under the drivers’ names. Jaguar did not expect to win but they wanted to prove the car and learn from the race results on how the model could be improved.

The three cars were: Chassis No. 660041 (Peter Clark / Nick Haines); Chassis No. 660042 (Peter Whitehead / John Marshall); Chassis No. 660040 (Leslie Johnson / Herbert (Bert) Hadley). Clark / Haines finished twelfth at an average speed of 80.6 mph (127 km/h), Whitehead / Marshall finished fourteenth and Johnson / Hadley retired with clutch failure after running for 21 hours; Johnson’s best lap time was 97 mph (156 km/h).

A Car for Le Mans

While the XK120 had shown that it could endure the long-running required at Le Mans, it was not the ideal car if Jaguar wanted an outright win. William Heynes and Lofty England discussed the matter with William Lyons who knew that a dedicated sports-racing car was the answer, but he wanted to wait until the Mark VII saloon was launched in October 1950 before making a decision. Heynes and England finally convinced him that a purpose-built car was the only way that Jaguar could hope for a victory in the French race. Lyons may have been keen on motor sport but he was also wary of the pitfalls that could befall an over-stretched company budget. He cited the fall of Bentley when questioned, but he knew that to establish the Jaguar name across the globe, without costly and ambitious advertising, a win at Le Mans would generate more than adequate press coverage and stamp Jaguar in the minds’ of a car-hungry public.

Financially Jaguar was in a good position, even though a works strike in 1950 had eroded some of the profits, and he gave Heynes and England the go-head to build a model specifically to win at Le Mans in June 1951. They had just seven months to design, build and prove a car from a clean sheet of paper and complete three examples ready to race. It is worth remembering that at this stage neither SS Cars or Jaguar had ever previously designed a racing car and were new to international motor racing. Also, Jaguar did not have a dedicated racing department, so one was established under Phil Weaver, with England organising and looking after the teams participating in the races.

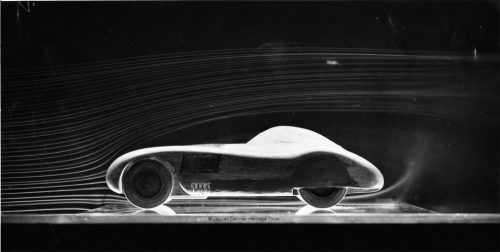

This wind tunnel model shows an early design for the proposed XK120 C, it has an enclosed driver’s canopy and rear wheel spats. Tests of the models showed that neither feature was required and they were deleted.

Initially, Lyons designed a body that he thought would be suitable and a small model was built. However, it was not right and he dismissed the design opting instead for one produced by Malcolm Sayer, who had recently joined Jaguar. Sayer had studied automotive engineering at Loughborough University and then joined the Bristol Aircraft Company where he was immersed in aerodynamics. Sayer’s brief was to provide a body that was aerodynamically efficient. His work at Bristol Aircraft during the war was valuable, as he brought a new dimension to Jaguar with his method of working out the required shape mathematically. This was something that had hitherto been alien to the automotive industry and immediately gave Jaguar an advantage.

Sayer retained his links with the aviation industry and took Jaguar into unknown territory with the use of a wind tunnel. This aspect of proving a design was something that had not been seen at Jaguar, or indeed any other British car manufacturer before.

Lyons wanted the racing car to resemble the XK120 and this gave Sayer a starting point, but in the event the final design bore little resemblance to the sports car but a family likeness remained.

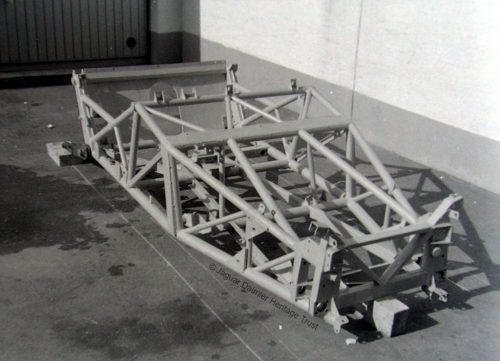

The strong tubular chassis frame for the C-type was designed by Bill Heynes and executed by Bob Knight and Tom Jones.

To save weight the heavy XK120 chassis was replaced with a tubular chassis frame designed by Heynes before handing over the detail design work to Robert (Bob) Knight. He got on with the drawings and in making a metal version (see image on the right) of Heynes’ proposal; the foundation of the chassis was a drilled channel-section framework to take a slightly-modified XK120 engine and the new body.

The strength of the design lay in a triangular box of tubes in the middle with sub-frames carrying the engine and front suspension. The crucial centre section, which contained the driver and passenger seats, was braced laterally, longitudinally and vertically. Heynes retained the XK120’s front suspension, but Knight extensively modified the rear suspension. The half-elliptical springs of the XK120 were replaced by a single transversely mounted torsion bar, connected to the live rear axle by trailing arms, while torque reaction members prevented lateral movement.

With the short space of time available to design and build a car for Le Mans, Lyons had three XK120s prepared with special lightweight aluminium bodies as a precaution against any possible delay with the Le Mans car. These lightweight XK120s were not required in France but two were later raced in North America, but they were not ideal and suffered overheating and braking problems.

William Heynes later recalled about the new Le Mans car: “We had about seven months to design, make and prove a car from a clean sheet of paper and to complete three cars for the race. We worked on drawings and models; we built up frames and bodies in wood and made use of broomsticks in the mock-ups of the tubular frames. Everyone involved would work extra hours and week-ends to get the work done.” Meanwhile, Harry Weslake (who acted as a consulting engineer to Jaguar) took a standard 3.4-litre XK engine, retained the wet-sump lubrication and the twin SU carburetters, but modified both the inlet port and the exhaust system; he introduced high-lift camshafts and a lighter flywheel. The modifications boosted the engine from 160 bhp up to 210 bhp.

Birth of the C-type

Small wooden models were made of Sayer’s design and tested in the wind tunnel. As data was gathered the models were subtly altered to give optimum airflow over the body. What finally emerged is arguably one of the most attractive Jaguars of any era. Known at Jaguar as the XK120C (for Competition) or Type C, the car soon became known as the C-type. Though to be accurate it should retain the factory designation of XK120C, but to avoid confusion we will refer to it as C-type. Abbey Panels, which supplied the XK120 bodies, made the various complex aluminium panels for the C-type and the car took shape in secret at the Jaguar works. As Heynes noted, from the initial chassis design to finished product the three hand-built C-types were ready in seven months. Some sources have stated that work commenced in September 1950, but with Heynes, Knight and Tom Jones (chassis) citing December 1950, it would seem the latter date is more likely.

Taken at Foleshill, seen here soon after assembly is C-type XKC 001; unpainted, engineless and without seats or instruments. From this print it is difficult to see if the bonnet had been given cooling louvres.

The first car to be completed, chassis XKC001, was tested by Jaguar test driver Ron Sutton at the Motor Industry Research Association test track near Nuneaton and at Silverstone. At the latter, Peter Whitehead, Peter Walker, Stirling Moss, Jack Fairman and Leslie Johnson were also able to try the car out before taking it to Le Mans. Somehow, the news of the C-type did not leak out and it was only revealed on 20 June 1951 by The Motor magazine when they ran a Jaguar press release and photograph.

Le Mans was just days away and the three cars were completed in time to be driven from Coventry to Le Mans. Lofty England, Jack Emerson and Phil Weaver drove the cars and they were accompanied by a Bedford lorry carrying spares. England, who ran the competitions department and would later take-over from Lyons as Managing Director, recalled at the time: “We wanted people to see that our cars were capable of being driven on the road, and if anything was going to fall off, then by the time you had driven across France on their bumpy roads, it would fall off. Much better to know before you start! Besides, driving there would save money.”

The three cars were entered for Le Mans by the drivers as Jaguar were concerned that if any disasters befell the C-types their name would directly be associated with any problem. They need not have bothered as from the start the C-type was the one to watch.

With Coventry trade plates the three Le Mans entries are from left to right: XKC 001, XKC 002 and XKC 003. This photograph was taken outside the Foleshill factory ready for departure.

The Jaguar C-types were the most modern-looking entrants that year but they were not regarded as much of a threat by the competition. During practice before the race Peter Walker averaged a promising 104 mph (167.4 km/hr) driving XKC 003, but there were problems, XKC 001 suffered engine trouble and had to be rebuilt by Jack Lea from Jaguar. The Marchal headlamps proved inadequate and more powerful examples were ordered, but they were slightly larger and new backshells in the body had to be made. England took on this task and, with Heynes and Phil Weaver helping, soon had them ready for fitting.

In practice Moss’s C-type struck the rear end of Morris-Goddall’s Aston Martin DB2 and England had to effect repairs on the nose of the C-type in time for the race. The three cars and drivers were: XKC 001 – 032 RW (Leslie Johnson and Clemente Biondetti), XKC 002 – 210 RW (Stirling Moss and Jack Fairman) and XKC 003 – 153 RW (Peter Walker and Peter Whitehead). Other entrants at Le Mans that year included: Allard, Cunningham, Talbot-Lago, Ferrari, Nash-Healey (driven by Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton who came in sixth), Aston Martin (Lance Maklin, taking third place after 257 laps), and Porsche making their first Le Mans appearance.

Le Mans 1951

Drivers sprint to their cars for the start of the 1951 Le Mans 24-hours Race. The four Jaguars, including Rob Lawrie’s XK120, are seen in the centre.

At four o’clock on Saturday 23 June 1951 the race started at a wet and overcast Le Mans. Stirling Moss, Peter Walker and Clemente Biondetti sprinted out to their C-types and were soon away. By the end of lap two Moss was second to one of the big Talbots and after three more laps he was leading with Biondetti in third place. After five hours Moss was still leading with the other two C-types in second and third positions. Moss also shattered the lap record at 105.24 mph (169.3 km/hr) in 4 mins 46.8 secs.

The Jaguars were going well, then Biondetti – race number 23 – noted a drop in oil pressure and pulled into the pits. It was found that oil was in the sump but none of it was being circulated as the oil feed pipe had cracked. Nothing could be done, as the rules at the time only allowed the use of parts and tools carried in the car; the C-type was retired but Moss / Fairman and Walker / Whitehead were still in first and second places.

On lap 94, Moss’s car – race number 22 – ground to a halt with a broken con rod, it appeared that a weld on the main oil feed pipe had broken due to engine vibration. Only the Walker / Whitehead C-type now remained in the race and it took the lead where it stayed to give Jaguar their first Le Mans victory. Peter Whitehead drove XKC 003 – race number 20 – some 45 minutes and 77 miles (124 km) ahead of the Talbot-Lago (Pierre Meyrat, who finished second having completed 258 laps). The Jaguar had covered 2,243.886 miles in 267 laps (3,611.0857 kms) at an average speed of 93.495 mph (150.461 km/hr). With this win Jaguar proved that its cars were fast and reliable and was hailed as a true enthusiast’s car. Helping cement the Jaguar name was Robert Lawrie, who entered his XK120 for Le Mans and finished eleventh.

This painting by Roy Nockolds of XKC 003 at speed in the rain

at Le Mans was commissioned by Esso Petroleum.

Esso presented it to William Lyons who hung it behind his desk at Foleshill and later at Browns Lane. It is now on display in the Collections Centre at Gaydon.

Before Le Mans 1951, Jaguar was a relatively unknown motor manufacturer, but after that win the name was emblazoned worldwide. Lofty once said: “As soon as we won Le Mans people knew what a Jaguar was and the name went forward very, very quickly.” The Company built on the victory and advertised the fact which boosted sales considerably. Other competitions were also entered for with the C-type and at the Dundrod Tourist Trophy Race, Moss drove XKC 002 into first place at an average speed of 82.55 mph (132.847 km/hr) with Peter Walker in second place and Tony Rolt in fourth place. Jaguar was awarded the Team Prize. It must be noted that, after racing and use as test vehicles, these three C-types were all dismantled by Jaguar and reduced to produce in 1952-53; they no longer exist.

Today Le Mans is still a major battle ground and speeds are far in excess of the 100+mph that Jaguar achieved in 1951 but seventy years’ later that Le Mans win is still regarded as the race that established a small Coventry company into a world leader.

Author: François Prins

© Text and Images – Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust