William Heynes

Jaguar’s Chief Engineer from 1935 to 1969

William Heynes

The remarkable and talented engineer who was crucial in developing the Jaguar marque.

Despite Swallow and SS Cars having been established for over ten years they lacked an in-house engineer. In the main, William Lyons relied on industry consultants, such as Harry Weslake, and on the Standard Motor Company’s own engineering department. While Swallow were content to manufacture bodies to fit existing chassis this was not a problem. Neither was it a major issue when, as SS Cars in 1931, they introduced their own design models with the SS I and SS II. These may have had Swallow-SS-designed bodies but the chassis and engines were sourced from the Standard Motor Company. The SS-designed models were successful and brought the Company to a wider market, but Lyons wanted to expand the range with a series of new models that would challenge the luxury car trade. However, at the time SS Cars did not have the necessary expertise to tackle the task and this called for a dedicated engineer to head a still-to-be-formed engineering department.

William Munger Heynes was born on 31 December 1903 in 11 Percy Terrace, Leamington Spa; initially he was educated by his maiden aunts who ran a school near their home. Later, from 1914, he attended Warwick Public School where he was considered a bright pupil and encouraged in his studies by his science master. Heynes later recalled that ‘ …he [the science master] noted that I had an aptitude for dissection and the ability to observe and draw, he sought to persuade me to embark upon surgery as a career. This, however, was not possible due to the financial burden it would place on our large family [and] would not permit the long periods of study required,’ Heynes was one of six boys. Leaving school in 1921 his family secured a ‘golden apprenticeship’ with the Coventry based, Humber Car Company in the drawing office. His younger brother was secured a ‘golden apprenticeship’ at the machine tool manufacturer Alfred Herbert.

Humber Cars and the Rootes Brothers

At Humber, under the guidance of Leslie Dawtrey and Edward Grinham, Heynes learned the motor business from design to completed car. Heynes was competent and a hard worker and in 1930 (aged 27) he was appointed head of the technical department. Humber had been established in 1900 and produced a variety of models from the small single-cylinder Humberette to the six-cylinder 30/40. World War One halted car production and when Humber resumed manufacture they produced a 15-hp model and later a light 8/18 popular car. As the Company prospered other larger models appeared and during Heynes’ early years with Humber he worked on several Humber designs, culminating with the significant Snipe 80, Pullman and 16/60. These were larger cars and were marketed at competitive prices for a growing market.

When the Rootes brothers bought Humber both Leslie Dawtrey and Edward Grinham left to join Standard Motors; Grinham as Chief Engineer and Dawtrey as his assistant. Heynes, meanwhile, worked on Rootes models and helped to develop an independent front suspension for the Hillman Minx. However, the board of directors, headed by the Rootes brothers, were content to leave matters as they were and retain the solid front axles for the Minx. Heynes contributed a four-speed gearbox, which was accepted and introduced on the Minx. As well as his work on Humber, Heynes was appointed to head the Hillman design office and occupied his time with stress calculations for the chassis frame. Heynes found the work interesting but routine and felt held back by the cautious Rootes board that seemed reluctant to change their existing engineering techniques.

Joining SS Cars as Chief Engineer

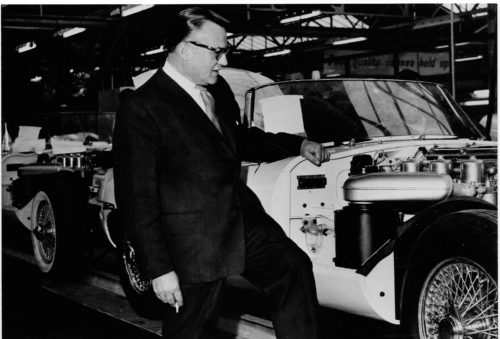

When Heynes joined SS Cars they had no technical department; here he is seen at work with his first engine test bed.

Meanwhile, William Lyons was looking for an engineer to join SS Cars. At Standard, Dawtrey and Grinham heard about this and remembered the gifted Heynes with whom they had worked at Humber; they suggested that Lyons interview their old student and later colleague. Lyons could see the benefit of the recommendation coming from these respected engineers. In his quest for an engineer Lyons saw and interviewed several potential candidates, interviewing some more than once. Heynes remembered he had five meetings with Lyons before he was offered the job.

Lyons told him that he wanted SS Cars to have its own engineering department and that he, Lyons, wanted to produce one of the world’s finest luxury cars. To this end he gave Heynes the task of engineering the project. This was balm to Heynes as he said at a lecture in 1960, that Humber had stalled and “…did not want anything new.” Lyons on the other hand did and he wanted it quite quickly.

Heynes was appointed as Chief Engineer for SS Cars on 1 April 1935. He was confident and knew he had to work carefully as, “I knew the work I was doing was going straight to the customer.” When William (generally known as Bill) Heynes arrived to take up his position at Foleshill he found that SS did not have a drawing office and there was only one draughtsman on staff. He quickly established a dedicated drawing-engineering office and, with Lyons’ approval, hired additional staff to get on with the new car that was expected to be ready by August that year.

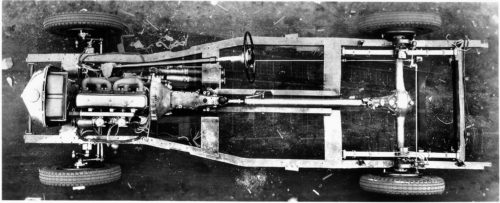

1938 – Heynes revised his original 1935 SS Jaguar chassis design to take the all-steel body.

Heynes had to design a new chassis suitable for the new six-cylinder engine, developed by Standard for SS, in a very short space of time. Heynes made the engineering drawings which were sent to Rubery Owen who were to manufacture the SS chassis. Heynes also adapted the chassis for the SS Jaguar 100 two-seater sports roadster and the smaller 1½ litre saloon, both of which were announced at the same time as the showpiece 2½ litre saloon to the general public at the London Motor Show on 24 September 1935.

The model was a success but Heynes knew it could be improved and, for the 1937 model year, he revised and widened the chassis frame for better legroom. For the following year the chassis was revised to accept the new all-steel bodies.

Gradually William Heynes built-up the engineering department and, with a small, dedicated team, continued to improve the SS Jaguar range of models, which included three saloons and two sports cars of differing engine sizes. SS Cars were in a healthy financial position when World War Two interrupted all car production in Britain. The Foleshill works were turned over to war production but a few SS Jaguar cars were produced in early 1940, before war production was increased.

William Heynes with Claude Baily, who joined SS Cars in 1940 as an engine designer.

Baily was another exceptional engineer and worked on the XK and V12 engines.

During the war years Lyons and Heynes, along with others, cast their thoughts to a post-war world of peace and new products, which included an in-house, not Standard-built, engine to power the models that were proposed.

Heynes led the team, which included Walter Hassan and Claude Baily, to design and build prototype four and six-cylinder overhead camshaft XK engines. After trials the resulting unit was given the prefix XK and went on to power, in various guises, Jaguar models for over forty years.

Heynes had not forgotten his Hillman independent front suspension (IFS) and designed a similar (but better) system for SS Cars in 1938. He admired the front suspension of the 1934 Citroën Traction Avant and was inspired by the French design which he used for the SS model. Heynes was always thinking ahead and this is shown to advantage by the use of ball-type king pin joints to locate and control wheel movement on the IFS. Heynes’ system was fitted to an SS Jaguar 3½ litre saloon (chassis No. XA 100) for trials and was driven extensively before the War ceased work.

Post War

Following the cessation of hostilities in 1945, the IFS was modified and installed in two experimental cars for further testing. Modifications included a coil-spring suspension with longer wishbones, but they were unsatisfactory and a return was made to the original idea of short top wishbones with lower arms operating longitudinal torsion bars. The stub axles were carried on ball joints top and bottom and the front suspension incorporated telescopic shock absorbers. Most of the development work on Heynes’ original design was carried out by Robert (Bob) Knight, who had joined Jaguar after the war. Following the war, Lyons had proposed to the Jaguar (as SS Cars were now known) board that Heynes be appointed to the board to replace Noel Gillett who had resigned; Heynes became a director on 30 May 1946.

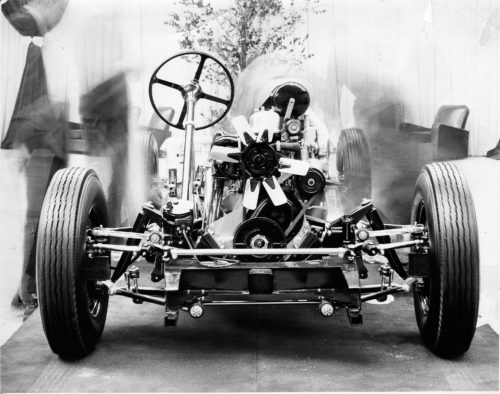

The 1948 London Motor Show – this Mark V chassis showed the new front suspension, with chrome-plated details.

Heynes had been tasked by Lyons to design a new chassis for the new post-war saloon and he wanted it to give an even more comfortable ride than the pre-war saloons had done. A Bentley Mark VI was bought and studied by Jaguar on how they could make their new saloon equally quiet and smooth.

With the independent front suspension in development and showing promise, Heynes was well aware that a new stronger chassis would be required to take the unit. It had to be rigid, as one that could flex would interfere with the efficient working of the suspension. A wheelbase of 120 inches (10 feet – 3.048 metres) that had been used on the outgoing saloons was retained and, to a degree, this dictated the design of the chassis, as did the use of the Salisbury hypoid bevel axle that had been introduced in August 1939. The front track was unchanged from the pre-war saloon at 56 inches (1.422 metres). What is immediately apparent from the above is that it is a sturdy and rigid structure, quite capable of taking a standard or coachbuilt body.

The new suspension and more rigid chassis made their debut on the Jaguar Mark V.

XK120 Launch at the 1948 Earls Court Motor Show

Also on the stand at the 1948 London Motor Show were examples of the 2-litre four-cylinder and 3½ litre six cylinder XK engine as well as the XK120 sports car. It was planned that the XK engine would power a new large saloon with a monocoque body (the Mark VII) but problems with the body supplier meant that there was no way this would be available for launch at the Motor Show. Lyons needed another car to showcase his new engine and decided to make a two seater sports car – what we would now describe as a ‘concept car’ – the XK120.

Heynes worked on the XK120 concept with Lyons from the start; he shortened the Mark V chassis and provided Lyons with the dimensions for wheelbase, engine area, passenger compartment and boot. As is well-known the car was conceived and built in a remarkably short time – around 3 months.

What is sometimes forgotten is that Heynes, Claude Baily and Walter Hassan worked closely with Lyons on the concept XK120. It was they who provided the technical specifications for Lyons to design and build the body that would give Jaguar a new market. Certainly, Lyons relied on Heynes as an engineer but, one suspects, also as an advisor on the actual shape of the XK120 as it changed from ungainly to sublime.

The XK120 was a real breakthrough for Jaguar on the international scene; the initial 200 cars proposed for production on ash frames with bought-in aluminium panels and hand-assembled had to give way to quantity production in steel. The story of the XK120’s success has been related elsewhere and does not require repeating here. Suffice to add that it was up to Heynes and his team to provide new drawings and production methods for the Jaguar workforce to manufacture the XK120 in quantity, at Foleshill alongside the equally popular Mark V. The saloon was the major profit earner and gave Jaguar a better financial base from which to develop the XK engine and the next generation range of models. From Heynes’ own writing it was clear that he did not want the XK100, powered by the 2-litre XK engine, and thought that Jaguar should emphasise the XK120, which they did by default as no one ordered the XK100.

During the War SS Cars had been involved in repairing battle damaged aircraft and getting them ready for a return to active duty. It was during these war years that both Lyons and Heynes became interested in the Dunlop disc brake that had been developed for RAF heavy bombers. With the earlier aircraft, which were lighter and slower, the need for powerful braking was not an urgency, however, as aircraft became heavier and faster a more reliable system of braking had been designed. This became even more essential with the advent of the fast jet-powered fighters, of which sections of Britain’s first examples – the Gloster Meteor – were being constructed by SS Cars at Foleshill. Naturally, the innovative braking system was of great interest to Heynes, as an engineer, and to Lyons, as a businessman with an eye on the future, for a post-war generation of cars.

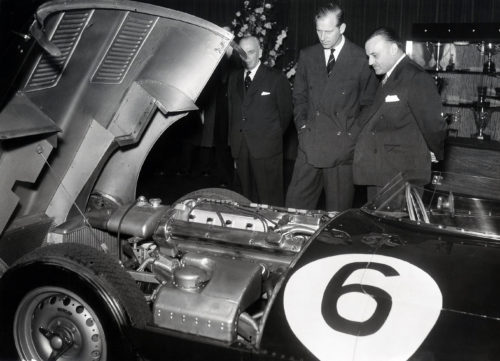

1956 Prince Philip Duke of Edinburgh is admiring the D-type with Heynes. To the left (slightly hidden) is director Edward Huckvale who joined Swallow in 1928 as Company Secretary.

Heynes was proud of the work that Jaguar did in conjunction with Dunlop to develop the disc brake for use on normal road-going cars. As with aircraft, cars were becoming more powerful and faster, the drum brakes of the time simply could not cope with advancing speeds. Jaguar used the Dunlop developed disc brakes on the C-type and later D-type.

At the 1953 Le Mans 24 hour race the ability to out-brake the competition, without suffering from brake fade, was the ‘secret weapon’ that gave Jaguar their 2nd Le Mans win. For a number of years their competitors continued to use drum brakes and Jaguar won at Le Mans again in 1955, 1956 and 1957 with disc-braked D-types.

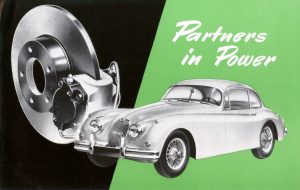

Dunlop ‘Partners in Power’ Brochure for the disc brake equipped XK150

The use of disc brakes in competition gave Jaguar valuable data on how the system performed, and after adding to their own and Dunlop’s testing using road cars, they perfected the disc brake for use on production cars. The first Jaguar sports car to be offered with Dunlop disc brakes was the XK150 with the Mark IX being the first saloon to have four-wheel disc brakes as standard. While Heynes was involved with the disc brake he also worked on anti-lock brakes with a view to introducing them to series production. He also worked on a fuel-injection system independently, as well as in consultation with Lucas, who later produced a system that was used by Jaguar and others.

Unitary Saloon – Project Utah

While the disc brakes were being developed, and buoyed-up with racing success at Le Mans and Reims, as well as the various rally wins by Jaguar cars, Heynes and Lyons considered entering the world of Formula One racing. In 1955 they discussed the subject at some length but after considering the high cost of designing, building and developing a dedicated model, as well as the revenue required to maintain a team, they came to the conclusion that Jaguar should stick to what they knew best, building cars and leaving the rarefied world of motor racing to others.

1955 – William Lyons and William Heynes at Browns Lane with an Austin-Swallow from 1930 and the new 2.4-litre saloon.

At the time there simply was no spare cash to fund a racing team and besides both Heynes and Lyons were too busy with Project Utah, a small XK-powered model that was soon to join the line-up as the 2.4 litre unitary saloon to fill the gap left by the demise of the 1½ litre Jaguar in 1948.

Heynes agreed the dimensions of the passenger compartment, wheelbase, engine bay and other technical requirements with Lyons so that work could commence. In their usual manner, Lyons, with Fred Gardner, dealt with the body style and shape and Heynes, along with Bob Knight, Tom Jones and others, concentrated on the mechanical side.

The 2.4 litre retained the proven front suspension but with coil springs attached to the lower wishbone. The dampers were situated inside the coil springs and both attached to a front subframe – there being no separate chassis. The subframe, probably the work of Bob Knight, also supported the steering gear and was attached to the body via V-shaped rubber bushes at the rear and vertical rubber blocks at the front. Heynes had devoted much time to the refinement of the unitary structure and to the silencing of road noise through rubber insulation.

One of the early prototypes was taken on an extensive test-drive programme by Heynes. As well as using it to commute between his home and Browns Lane, he also took it to France on his annual holiday. This extended trial on various road surfaces and conditions gave the engineer valuable data to be added to the one accumulated by Norman Dewis and the team at MIRA and on chosen routes in the Midlands and Wales. This model was important to Jaguar and set the stage for the cars that followed in-build at Browns Lane. It also gave the marque a new market in North America.

A feature that Heynes promoted, and something that Lyons was not keen on, was air conditioning for the US market. Following the war, many cars in that country had been offered with air conditioning as an option. Heynes had an Arctic-Kar system imported to Browns Lane and fitted to a works Mark VII. Tests were positive and US dealers could offer the option installed in the Mark VIIM at $595. It was another first for Jaguar and as the years went by air conditioning became standard for North America; even the E-type Roadster and Coupé, after work in the engine bay, was given the optional extra.

Moving On

1961 Bill Heynes beside the track at Browns Lane with E-types bound for export.

In the Experimental Department was a small two-seater sports model that was due to take over from the XK150; this was being developed by the team led by Heynes into what would become the Jaguar E-type.

The path from design to introduction was not easy as many new engineering facets were being trialled for the sports model and for Jaguar in general. One of the most innovative was the use of an Independent Rear Suspension (IRS) system that had been designed by Bob Knight. Heynes encouraged Knight with this work and in any conversation or press call always credited him for the IRS that gave Jaguar a march on its competitors.

It was this IRS system that gave the E-type its outstanding road holding abilities when it was launched in 1961. This combined with the renowned XK engine and the disc brakes put the E-type in a class of its own, for less than half the cost of an Aston Martin, and a third of the price of a Ferrari.

When the Mark X saloon was launched in October 1961, it too had the IRS system and evolutions of this have contributed to the ride and handling of Jaguar cars for many decades.

In 1960 Jaguar bought the Daimler business and gained extra manufacturing space at Radford in Coventry, not far from Browns Lane. They also inherited the SP250 sports car and two Daimler designed V8 engines. Heynes, Walter Hassan and Claude Baily spent time investigating the small-block unit and came to the conclusion that it was not right for Jaguar and they were not impressed with the design and besides they were now working on their own production V12 engine, for which Heynes and Baily had already made the first drawings. This would have an impact on the next stage of Jaguar’s engineering.

Jaguar looked at the world of Formula One racing again in the early 1960 but, once more, decided against it. There were even talks with Colin Chapman and Lotus with a view to buying the firm along with the motor racing business but Chapman changed his mind and called the whole idea off. Jaguar considered Le Mans and Heynes talked with Lyons and the board about a car for the endurance race. As early as 1952, Heynes and Baily had married two six-cylinder engine heads to produce a 4.9-litre V12 for test purposes. Encouraged, Heynes asked Baily to begin drawing up V12 schemes for two different applications, one for sports car racing – primarily Le Mans – and the other for road cars. By the mid- to late 1950s Lyons had in mind a new range of large saloons and for this the smooth V12 would be ideal.

The resulting Le Mans car was the XJ13 which was begun in 1964 and completed in 1966, powered by a four-cam, 5.0-litre competition engine. This was to comply with the then-current Le Mans prototype-class capacity limit, but by the time the XJ13 was finished, a reduction in engine capacity to 3.0 litres, meant the XJ13 was not destined to go to Le Mans. Rather than use it for racing the XJ13 was developed as a mid-engined racing prototype for use as a test-car. This superb model was built and tested but was then put into storage in the Experimental Department. Malcolm Sayer, who had styled the body, also designed another version with, as Heynes said: “A different body, more streamlined and long, but it was never built.”

Changing Times

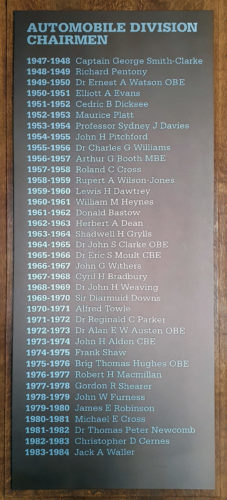

Institute of Mechanical Engineers – Automobile Division Chairmen

WM Heynes 1960-61

By the 1960s, Sir William Lyons had been considering a saloon that would sit in-between the Mark II and Mark X / 420G models but would be more advanced in engineering terms. He discussed the mechanical requirements with Heynes who then briefed his team on what was expected. In place were the XK engine and IRS, these formed the basis of the new car coded XJ4 by Jaguar. Heynes’ highly-capable team provided the measurements, wheelbase, height, weight, tyres etc for Lyons to match with a body of his design. When the design was in a more defined state Lyons would show it to Heynes, England and others for their opinion.

The new saloon took time to get right and it was not until 1968 that it was announced as the XJ6; from its introduction it was hailed as a major triumph in terms of engineering, looks, comfort and as a driver’s car. Heynes and his team had worked hard to make the XJ6 the very best Jaguar of all. Indeed, after road tests the motoring press dubbed it ‘The Best Car in the World’ and the customers soon ordered the XJ6 in quantity. Heynes recalled in an interview in 1970: “Our XJ objective was to modernise the design from the 420s, say, to improve the handling and particularly the silence and road noise. Generally we aimed to produce a car which engineering-wise could compete with Mercedes.”

Heynes had now been with SS Cars and Jaguar for over thirty years and in that time had, in his quiet way, brought about tremendous changes to the marque. He was involved in all aspects of the engineering side of Jaguar and those who worked with him have commented on how much he contributed to their ideas and innovations. Heynes did not stand up and grab the limelight whenever Jaguar was in the news, he was content to know that he had helped to make things happen.

Within the industry he was greatly respected and in his field of automotive engineering he was held in high esteem. He gave lectures to the Institute of Mechanical Engineers and even in these he was modest and gave credit to those who had helped with a particular development or invention for Jaguar. For his contribution to automotive engineering he was awarded the prestigious James Clayton prize in March 1959 and he was elected Chairman of the Automobile Division of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers from 1960-61.

Heynes was not one to take a back seat and let others do the work; he was always looking at methods on how the models could be improved and also on how building the cars on the production line could be made more efficient. Not by any time and motion study but by considering the various components and how they came together during build.

Retirement

At the time of the XJ6 launch in 1968 Bill Heynes was sixty-five-years-old and in 1969 he was made a CBE; at the end of that year he retired as Vice Chairman and Technical Director of Jaguar Cars, after 35 years.

Heynes left Jaguar to concentrate on running the farm he owned near Stratford-on-Avon. In retirement he kept in touch with his former colleagues at Jaguar and took an interest in the line-up of models. He recalled that the XJ-S body had been laid down before he left but was a long way from completion and was emphatic that it was “…not a replacement for the E-type and although the tyres are the same size, they are not the same type.” Unfortunately, when Jaguar was struggling to survive under the British Leyland banner, people like Heynes and Lyons were completely forgotten and ignored. Happily, this situation changed when Jaguar became independent and (Sir) John Egan went out of his way to engage with the ‘old guard’ whom he considered were vital to the overall well-being of the Company.

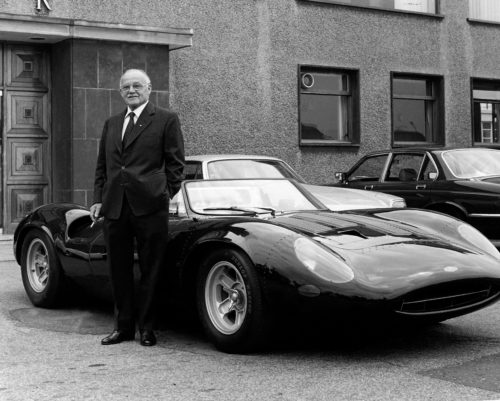

Heynes kept in touch with Jaguar and his former colleagues.

In 1980 he returned to Browns Lane to be reunited with the rebuilt XJ13, a model he developed with Malcolm Sayer.

In the JDHT Archives are various letters from Lyons and others to Egan and one from Heynes thanks Egan for his thoughtfulness in sending a Jaguar and driver to take Heynes and his wife shopping once a week. Heynes had given up driving and this act by Egan was not company policy but shows the respect that the Jaguar Managing Director (and his board) had for the man who had worked tirelessly with Sir William in creating a world brand. Heynes enjoyed his retirement and continued with his farming interests, but after the death of Mrs Heynes, ‘Dutch’ to Bill and their friends, Heynes slowed down and declined in health.

William Heynes died in July 1989.

John Dugdale got to know William Lyons and Bill Heynes through his work as a journalist and later as an employee with Jaguar North America. He wrote: ‘Lyons’ chief engineer, Bill Heynes, in contrast to his chief, was always quiet and contemplative, short but tough. His engineering advances were evidently considered with much thought and thoroughness. His immense output under the stress of the business, that is, the development of new models always against time, and the subsequent overcoming of technical problems, proved him to be a determined and masterly engineer.’

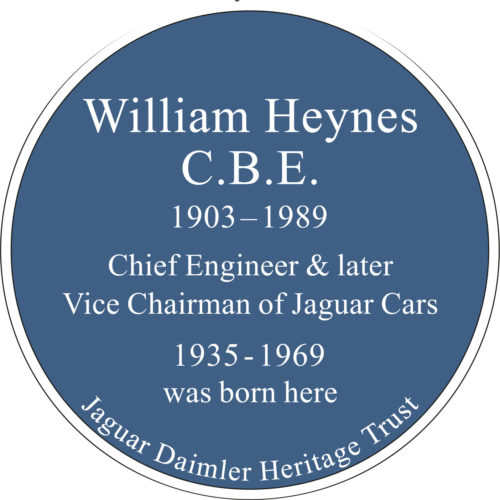

Postscript – 11 Percy Terrace – Blue Plaque – 28 September 2022

Blue Plaque unveiled

28 September 2022

Jonathan Heynes & Cllr Nick Wilkins unveiling the plaque

On the sunny afternoon of Wednesday 28 September 2022 a blue plaque was unveiled by the Mayor of Leamington Town Council, Cllr Nick Wilkins, on 11 Percy Terrace commemorating William Heynes.

In attendance were: the owners of Number 11 – Mark Roberts and Trish Lund; Jonathan Heynes (William’s son) and other members of the extended Heynes family; the Mayor and Katherine Geddes from the council; Matthew Davis, Maggy Haynes and Tony Merrygold from the management team of the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust (who funded the plaque); and members of the Leamington History Group – who helped co-ordinate everything.

Following the unveiling, both the Mayor and Jonathan Heynes gave short speeches covering both the importance of blue plaques in Leamington and the life and work of William Heynes. The attendees were then invited to join the Mayor for refreshments in the Council Chamber at Leamington Town Hall.

After tea, coffee and an excellent selection of cake, Tony Merrygold delivered a brief appreciation of William Heynes, summarising his career, his rise from apprentice to Chief Engineer at Jaguar, through to him being awarded a CBE and his retirement in 1969 as Vice Chairman of the Company.

Authors: François Prins with additional information from Jonathan Heynes and Tony Merrygold

© Text and Images – Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust

Sources and Further Reading:

-

Parker, Chas and Porter, Philip, Jaguar C-Type: The Autobiography of XKC 051 (Porter Press International Ltd, 2017)

-

Porter, Philip and Page, James, Jaguar Lightweight E-Type: The Autobiography of 49 FXN (Porter Press International, 2017)

-

Harvey, Chris, E Type: End of an Era (The Oxford Illustrated Press 1977)

-

Grimsdale, Peter, High Performance: When Britain Ruled the Roads (Simon & Schuster UK, 2020)

-

Mennem, Patrick, Jaguar: An Illustrated History (The Crowood Press Ltd, 1991)

-

Parker, Chas, Jaguar D-Type: Owners’ Workshop Manual – 1954 Onwards (All Models) (Haynes Publishing, 2017)

-

Elmgreen, John, Jaguar D-Type: The Story of XKD 526 (Porter Press, 2020)

-

Whyte, Andrew, Jaguar: The Definitive History of a Great British Car (Patrick Stephens Limited, 1990)

-

Hull, Nick, Jaguar Design: A Story of Style (Porter Press International, 2015)

-

Daniels, Jeff, Jaguar: The Engineering Story (J H Haynes & Co Ltd, 2004)

-

Porter, Philip, Jaguar: E-Type The Definitive History (Porter Press International, 2015)

-

Martin, Brian James, Jaguar: From the Shop Floor (Veloce Publishing Ltd, 2018)

-

Thorley, Nigel, Jaguar in Coventry: Building the Legend (Breedon Books Publishing Co Ltd, 2013)

-

Berry, Robert, Jaguar: Motor Racing and the Manufacturer (Distributed by E.P. Dutton, 1978)

-

Porter, Philip, Jaguar: Sports Racing Cars (Bay View Books, 1995)

-

Skilleter, Paul, Jaguar: The Sporting Heritage (Virgin Publishing, 2001)

-

Skilleter, Paul, Norman Dewis of Jaguar: Developing the Legend (PJ Publishing Ltd, 2017)

-

Porter, Philip and Skilleter, Paul, Sir William Lyons: The Official Biography (Haynes Publishing, 2001)

-

Porter, Philip, Stirling Moss: The Definitive Biography – Volume 1 (Porter Press International, 2016)

-

Bingham, Phillip, The All-American Hero and Jaguar’s Racing E-types (Porter Press International, 2020)

-

Porter, Philip, The Most Famous Car in the World: The Story of the First E-type Jaguar (Cassell, 2000)

-

Wilson, Peter D., XJ13: The Definitive Story of the Jaguar Le Mans Car and the V12 Engine That Powered It (PJ Publishing, 2011)