RACING JAGUARS – Broadspeed XJC V12

Reproduced with permission of Octane magazine (April 2014)

Octane 2014 April Broadspeed XJC V12 Pages 106 & 107

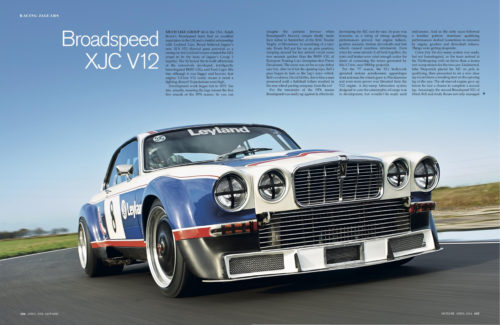

MUCH LIKE GROUP 44 in USA, Ralph Broad’s Broadspeed team had an excellent reputation in the UK and a fruitful relationship with Leyland Cars. Broad believed Jaguar’s new XJ-S V12 showed great potential as a racing car, but Leylands’ execs wanted the XJ12 coupé to be the basis of Jaguar’s Group 2 hopeful. The XJ lacked the in-built athleticism of the extensively developed, intelligently homologated BMW CSLs and Ford Capri RSs but, although it was bigger and heavier, that mighty 5.3 litre V12 surely meant it stood a fighting chance? Expectations were high.

Development began in 1975. Too late, actually, meaning the Jags missed the first five rounds of the 1976 season. So you can imagine the patriotic fervour when Broadspeed’s brawny coupés finally made their debut in September, at the RAC Tourist Trophy at Silverstone. In something of a fairy tale, Derek Bell put his car in pole position, romping around the fast airfield circuit some two seconds quicker than the the BMW CSL of European Touring Car Champion-elect Pierre Dieudonné. The scene was set for an epic debut race but, after he’d led the opening laps, Bell’s pace began to fade as the Jags tyres wilted. Bell’s co-driver, David Hobbs, drove like a man possessed until a halfshaft failure resulted in the rear wheel parting company from the car!

For the remainder of the 1976 season Broadspeed was really up against it, effectively developing the XJC race-by-race. Its pace was fearsome as a string of strong qualifying performances proved, but engine failures, gearbox seizures, broken driveshafts and lost wheels caused countless retirements. Even when by some miracle it all held together, the tyres and brakes soon cried enough under the strain of containing the forces generated by the 1.7 ton, near 500 bhp projectile.

For the ’77 season the XJ’s bodywork sprouted serious aerodynamic appendages front and rear, the wheels grew to 19 in diameter and even more power was liberated from the V12 engine. A dry-sump lubrication system designed to cure the catastrophic oil surge was in development, but wouldn’t be ready until mid-season. And so the early races followed a familiar pattern: dominant qualifying performances dashed (sometimes in minutes) by engine, gearbox and driveshaft failures. Things were getting desperate.

Octane 2014 April Broadspeed XJC V12 Page 108

It weighs nearly two tons and the body is obviously pumped up and be-winged for racing.

Come July the dry-sump system was ready, but not homologated, so the team arrived at the Nürburgring with no fewer than a dozen wet-sump motors for the two cars. Undeterred, John Fitzpatrick placed his XJC on pole in qualifying, then proceeded to set a new class lap record from a standing start on the opening lap of the the race. The oil-starved engine gave up before he had a chance to complete a second lap. Amazingly, the second Broadspeed XJC of Derek Bell and Andy Rouse not only managed to finish the race, but did so in second place. It would be the big Jag’s best result in two troubled seasons, Leyland pulling the plug before the end of the ’77 European Touring Car Championship. It was a sad end to a blighted project.

This is the car that finished second at the Nürburgring. Like all Heritage’s competition cars, it is timewarp original. None is raced, but they are used for demonstration runs. This means they’re kept in good fettle, but haven’t had the rebuilds and continual development that most of today’s grids of so-called historic racers have been subjected to. They also run on wets, not slicks, and are driven with an appropriate degree of respect, which is just as it should be with living museum pieces.

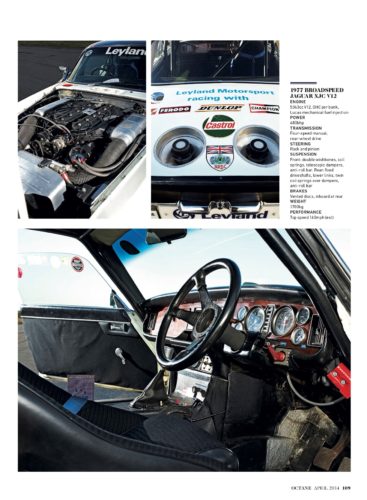

This XJC is still a curmudgeonly beast to run. It spits and coughs in protest as JDHT’s Richard Mason tries to tickle it into life, using an impressive mixture of empathy and choice words. Content that the Lucas mechanical fuel injection system is behaving itself, he drops the huge bonnet, opens the driver’s door and straps me in. After the rudimentary cockpit of the E-type, the XJC’s is amusingly true to the road-car’s, a scattering of white-on-black dials sitting in a huge walnut veneer dashboard!

All the controls are heavy, the clutch and steering especially so. Trying to manouevre at low speeds is a real tug of war, but at least the clutch isn’t grabby. If the cockpit is rather genteel, the engine is an absolute animal. When it fires the noise is all-consuming; a big, industrial blare that punches into your skull and pummels your chest cavity. I’ve never experienced anything like it.

The four-speed manual transmission is slicker than I’m expecting, the hefty metal gearknob slotting through the H-pattern gate without any snags or grinding of teeth, thanks to synchromesh and a precise fluid action. If only the unassisted steering were equally user-friendly. I’d rather hoped it would lighten with speed, but it’s still incredibly heavy and you really have to grip the steering wheel tight, grit your teeth and work it with as much muscle as you can muster.

All is forgiven when you can open the taps. The XJC yelps forwards as the revs build, each gear devoured in a cataclysmic explosion of noise and accelerative g. With those massive tyres – 14.5 in wide at the rear! – generating enormous traction, it really does put every last horsepower (rumoured to be 550 bhp, but in reality no more than 480 bhp) to the tarmac. Even the long stride of fourth gear only slightly takes the edge of its appetite for the horizon. I’m careful not to take liberties with the Heritage’s generous 6,000 rpm limit, but it’s horribly tempting to keep my foot buried and not throttle back, a little over halfway along Blyton Park’s main straight. This thing accelerates like an avalanche.

All of which places rather more emphasis on stopping than I’d like, especially with nothing but a ploughed field for run-off. To keep this beast in check Broadspeed fitted twin four-pot calipers to the front discs, which Group 2 regs limited to a measly 300 mm diameter. But it was nowhere near enough; the twin calipers exacerbated heat build-up, and the inboard rear discs overheated and caused driveshaft fatigue. The thought of trying to slow this thing at a track like Monza is frankly terrifying.

Octane 2014 April Broadspeed XJC V12 Page 109

The walnut-veneered dashboard rather touchingly remains in place.

It’s wholly fitting that the XJC develops a fuelling problem that curtails the second of my sessions. But no matter, I’m already totally smitten by this old warhorse. As I climb out and take one last admiring glance it looks anything but a failure, standing before me defiant and proud, its awesome, thuggish physique for once giving the lie to the old motor sport adage, that if it looks rights, it is right. History might have indelibly marked its card as a loser, but if like me you’re a sucker for a story of what might have been you’ll prefer to think of this extraordinary red, white and blue brute as a winner-in-waiting.

|

1977 BROADSPEED JAGUAR XJC V12 |

|

| ENGINE | 5,343 cc V12, OHC per bank, Lucas mechanical fuel injection |

| POWER | 480 bhp |

| TRANSMISSION | Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive |

| STEERING | Rack and pinion |

| SUSPENSION Front: | Double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar |

| SUSPENSION Rear: | Fixed driveshafts, lower links, twin coil springs over dampers, anti-roll bar |

| BRAKES | Vented discs, inboard at rear |

| WEIGHT | 1,700 kg |

| PERFORMANCE | Top speed 160 mph (est) |